A floating lab on Loktak Lake, about 50 km from Imphal

A floating lab on Loktak Lake, about 50 km from Imphal

“LET’S SAY, the lake has not been to the ICU as yet,” says Dinabandhu Sahoo, seated in a custom-made blue boat on Loktak Lake, over 50 km from Imphal. “But why wait for that to happen? It’s better to take a precautionary step.”

Sahoo is the director of the Institute of Bioresources and Sustainable Development (IBSD) in Manipur. Funded by the Department of Biotechnology, the ‘Floating Laboratory’ he is seated in is part of a larger network to monitor the health of water bodies in the Northeast. It’s also a first in a major initiative that could be replicated across the region to monitor the rising pollution in its water bodies and put in place preventive measures.

The next stop is the Brahmaputra river, which see ‘floating B4 boats’ cruising over it. The Brahmaputra Biodiversity and Biology Boat, B4, will take the shape of a “large barge” set up on the river with a well-equipped lab including cold storage facilities for holding samples, along with multiple satellite boats or rafts that will venture into shallower and narrower parts of the river to lift samples. The department had announced an initial investment of Rs 50 crore for the project.

The floating lab on Loktak Lake is like a satellite boat that travel across to 15 different spots, picking up water samples to test for a series of parameters. It is a low-budget, low-cost initiative for now.

Speaking to The Indian Express, DBT senior advisor T Madhan Mohan said, “The idea was to float a large boat that will serve as a place to conduct experiments and research on the Brahmaputra, and address problems that affect the aquatic life. What we see on Loktak is to check water quality and the excessive growth of biomass that can affect the health of the lake.”

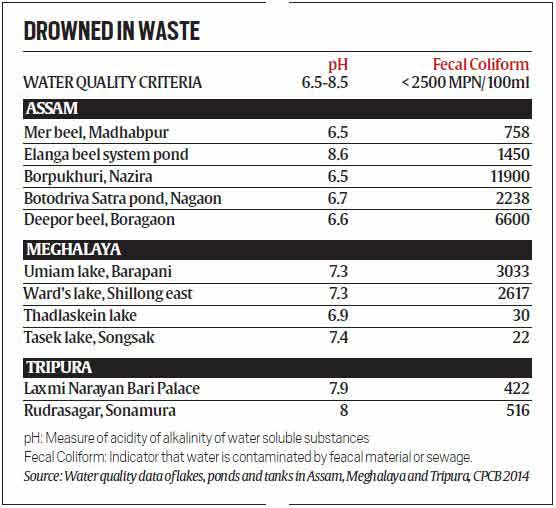

Back at Loktak, Sahoo explains the threat to the lake. The striking tourist attraction has over the years begun to exhibit the strains of being the dump-yard of a fast urbanising state capital. “Untreated sewage and chemical waste from the nearby paddy fields has led to the increase of biomass in the lake: from normal to excessive levels,” he says.

In other words, pollution levels if it goes unchecked at the lake, which is a natural catchment for rainwater, could have dire consequences. With cascading effects on the health of people who live on the unique “floating islands” or phumdis, the aquatic life and wildlife, people’s livelihoods and the fowl smell that it could lead to might potentially keep away the large number of tourists that the lake attracts.

“Much of the focus is on carbon dioxide levels in water bodies, but nitrogen is fast catching up as a significant pollutant,” says Sahoo, adding that is beginning to show its effects on Loktak’s aquatic life. At the dock, from where boats leave carrying visitors to spend a few hours enjoying the scenery and breeze, mounds of biomass line the side of the approach road. Biomass in fact makes up the foundation of that road, say workers at the dock.

Since February 24 this year, a team of six researchers, of which five are women and majority in their twenties, have visited the lake in sets of two, three times a week, to dip beakers into the lake, for testing the waters. “Before we got our own boat, we hired a boat for three months to pick up samples,” says 28-year-old senior research scholar Kikku Kunui, who says she is originally from Chhattisgarh.

Skilled staff is a huge challenge here, says Sahoo, “everyone in my team has been educated outside Manipur and have then returned to work here.” Kunui, her colleague Rajkumari Supriya, both wearing purple gloves pull out a sensor from a suitcase that holds all the equipment, one of them dips a medium sized beaker into the lake to collect a sample. “We test for temperature, pH levels (a measure of acidity), conductivity, dissolved oxygen, and we plan to start testing for turbidity too,” says Supriya.

While all this is done on the boat itself, back in the institute, samples are tested for biochemical oxygen demand, chemical oxygen demand, chloride and levels of phosphate and nitrogen. The quick checks the researchers do on a Saturday afternoon, throws up elevated levels. For instance, the pH of the lake varies from 6.8-7.2 — the healthy limit is around 7. “Even a 0.1 increase in pH can cause decalcification,” Sahoo says, adding the data that will be collected and collated with an aim to eventually affect policy.

To Supriya’s left, a bamboo hut constructed on a large phumdi — an island of mud and vegetation that acts like a thick carpet on the water — lulls in the midday breeze. It is proof that the lake supports human life and provides the resources for cooking, cleaning, fishing and a foundation for resting on.

The core team of researchers works alongside families who live on these phumdis, and practice what they term “need-based science,” often speaking to the families about what it is they are out there to do. “Families consume this water for bathing, cooking their food and growing their vegetables, so it is important to make sure they know what quality of water they are using,” says Kunui.

“We come out here early and stay till about 4pm. It gets dark here earlier. In that time of the 15 spots where we collect samples from, we try and get through as many.”

Some distance away, voices rise from a circular phumdi that holds a large fishing net forming a giant fish trap. The men adjust the fishing net, the women sit on a narrow boat watching them. In a large cage, their livelihood — fish — thrash about gasping for air, half submerged in a lake which itself is in danger of losing its life.