https://www.timesunion.com/opinion/article/Rex-Smith-Walls-that-protect-also-restrict-us-12760326.php

https://www.timesunion.com/opinion/article/Rex-Smith-Walls-that-protect-also-restrict-us-12760326.php

Rex Smith: Walls that protect also restrict us

Published 10:10 pm, Friday, March 16, 2018

Walls that are built to protect us likewise restrict us. That's the risk when we build a wall: We may preclude a profit, or block a blessing.

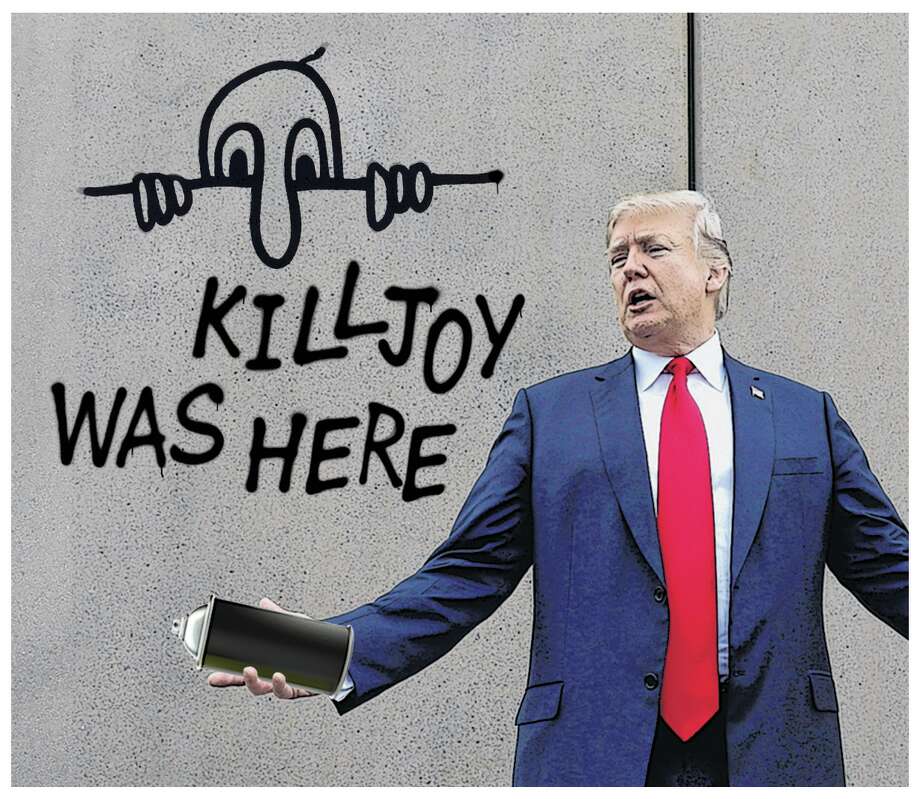

This week our president visited a parched patch of land near San Diego to inspect eight 30-foot-high slabs, prototypes for the "big, beautiful wall" between Mexico and the United States that he often promised on the campaign trail. His stated goal is to protect the United States from "criminals" and "rapists" who he says are crossing the border unimpeded.

All the other news of the week, though, almost obscured what was clearly intended by the White House to be a moment to focus attention on what may turn out to be the monument to Donald J. Trump's presidency, the Great Wall of the Americas.

A wall along all 2,000 or so miles of the nation's southern border, dividing two of the three nations of the North American continent, would be simply a silly idea, of course, if it weren't for the ways it will cost us: that is, beyond the $18 billion that the administration has asked Congress to pony up (less than half the cost projected by independent analysts), but, more significantly, the toll the wall will take on the spirit of cultural sharing and openness, not to mention the opportunities for economic growth, that a confident America could project, and that a better America surely would.

Actually, it wasn't the president's visit that got me thinking about the wall, but rather a few hours spent on the Siena College campus Thursday evening, attending a talk and reading by the Mexican-American writer Luis Alberto Urrea (pronounced oo-RAY-uh). Urrea's new novel was released last week, but the timing of his visit to Siena was coincidental; he was there to deliver the annual Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King Lecture on Race and Nonviolent Social Change.

Urrea grew up on the border of the U.S. and the edge of poverty, almost within sight of the eight sample walls. Between his words and those of the Rev. King that hung in the air in the Siena ballroom, surely few in the crowd of several hundred there left with a view that the wall is in any way sensible.

There are the practical matters, certainly. Lots of the border is rough terrain that can't accommodate a three-story wall. And if you're being practical about your politics, the fact is that polls show American taxpayers, by a wide margin, don't want to spend billions of dollars on a wall — money that could go to something more useful, such as, well, almost anything else.

But what Luis Alberto Urrea spoke of was life along the border. He lived on both sides, the son of a tough Mexican father and a mom he describes as a New York socialite. Suffering from tuberculosis as a child, Luis moved with his family to the U.S. side so he could get medical care. If he sounded like a kid from Tijuana, he looked more like a Dubliner, pink-cheeked and blue-eyed. He has always bridged cultures, a foot on each side of the land that the Trump wall would bisect.

So Urrea knows the impulse to cross the border; it was a daily fact of life where he grew up. The nearby San Ysidro Point of Entry is the busiest land border crossing on Earth: 56,000 vehicles and 20,000 pedestrians a day.

"People don't understand the point of view of those who seek solace and shelter in our country. People who come to this country — it's a love song to our country," Urrea said at Siena. "It is an act of faith in the promise of our country, which many people, sadly, believe is dead and gone."

As a boy, Urrea thought he would become a priest, so it's not surprising that he speaks comfortably of scripture, and says that he fantasizes about a "Bible-off" with those who want to close the door to immigrants, including the poor ones.

"I want them to show me the place in the Bible that tells us not to welcome the visitor," he said, "where it tells us to not feed the hungry, not clothe the naked child, not care for the prisoner."

It's not that we shouldn't have secure borders. Of course we should. By and large, we do: Border apprehensions have been falling for years, as fewer people have tried to cross illegally. If we want to tighten control, we could hire a thousand more agents to patrol vulnerable spots and install more high-tech sensors for a lot less than $40 billion.

But the Great Wall of the Americas isn't really about security; it's about preying on the fears of people unsettled by decades of social and demographic change, and reinforcing the fake notion that immigrants are a threat to a way of life we cherish.

That American life has always been about openness and freedom, not walls and fear, and about greeting people like the blue-eyed kid from Tijuana with an open hand, not a fist. At Siena the other night, at a lecture named for America's greatest 20th-century voice for freedom, that point was well understood.