Hosting futuristic hypercars born of collaborations with Alfa Romeo and Ferrari, as well as iconic cars of the Italian heavyweights from the 1940s, '50s and '60s to celebrate its 80th anniversary, Pininfarina's museum highlights all the best work of a design powerhouse.

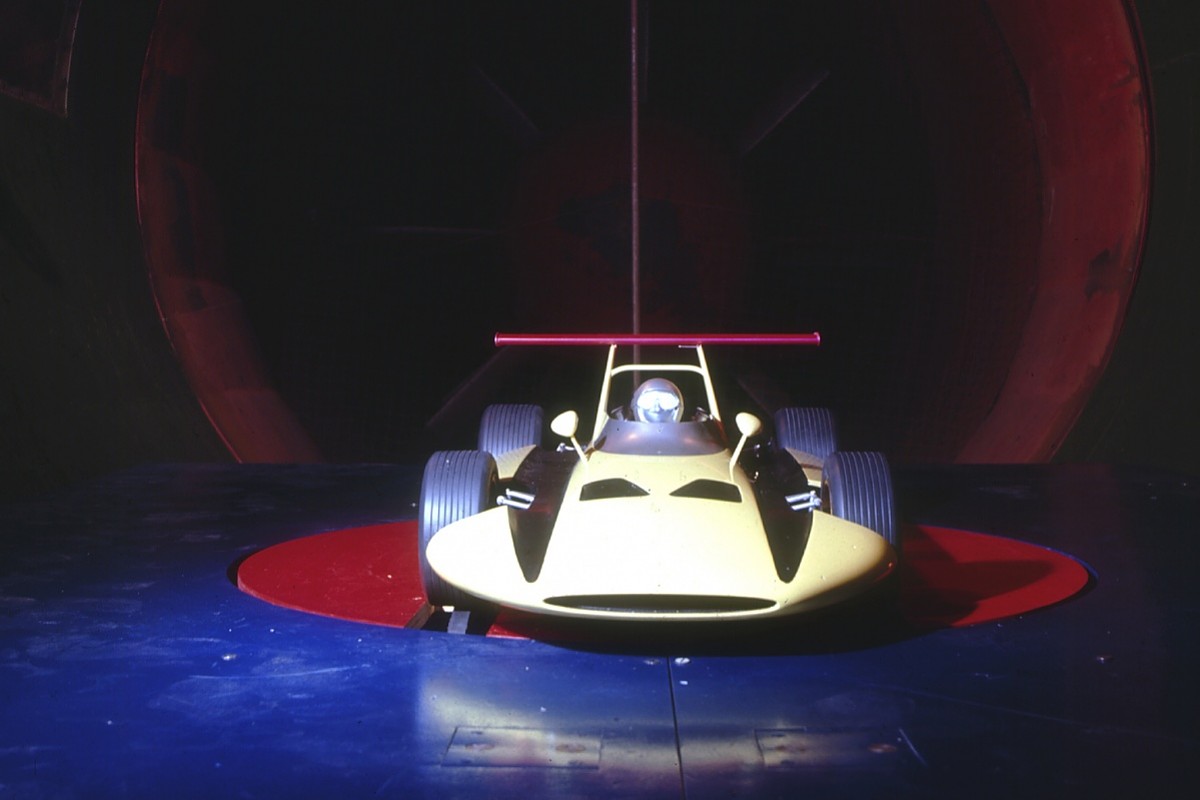

Right at the back, it's also home to a bizarre 'Formula 1' car. Ask around, and few can tell you much about it.

While the biographies of its road cars are comprehensive, a quick glance around to the side of this curious design's exposed V12 tells an observer its name - 'Sigma' - but little else. As it transpires, several of the advances the Sigma brought were well ahead of their time, to the point that some of its safety innovations did not appear in F1 until a decade later.

Odd, considering it came in the context of F1's long-running battle with, or more accurately against, safety in the 1960s.

That period resonates with an extract from Jackie Stewart's autobiography, and it's not the famous Nurburgring victory of 1968, the slipstreaming spectacular at Monza a year later or the highs and lows of his Tyrrell days. It's his crash at Spa in '66.

Caught out by a pool of water at 170mph, Stewart's BRM hit a telegraph pole and landed upside down in a ditch with a ruptured fuel tank. Amazingly he was unharmed, having been a spark away from being stuck in a car on fire in a period of F1 that was incompetent in its attempts to prevent such calamities. It was a turning point for the Scot, who afterwards campaigned vociferously to improve safety measures.

One year later at the Monaco Grand Prix, Lorenzo Bandini was not so lucky after his Ferrari crashed at the chicane and burst into flames. Bandini died in hospital three days later as a result of the burns he suffered while trapped underneath the car.

It was another needless fatality, and there would be one for every eight races in the 1960s. While Stewart continued his campaign, an unlikely source in Italy decided to do something about it. It probably wasn't Ferrari, but it certainly utilised a relationship with the F1 heavyweight. Instead, it was renowned design house Pininfarina that took on F1's safety issues.

So Ferrari came to Pininfarina's Turin base in 1968, allegedly at the behest of il Commendatore Enzo, who had had enough of F1's lack of safety. And it came in pieces, in the form of the 312 F1 car. Pininfarina was given its 400bhp V12, the bare chassis, a five-speed gearbox, a pedal and four wheels. Pininfarina was essentially given a Tamiya model kit and told to build an F1 car.

Considering that Pininfarina did not have a single employee with F1 experience, it was as if Ferrari had lent back over and pinched the manual too. Now it had to build a car that would redefine safety standards going into the 1970s.

How much the FIA and rival teams knew of this is disputed by various people involved in the project, but what is clear is that Swiss magazine Revue Automobile was central to the project and involved throughout.

Paolo Martin, who became known for designing the Ferrari Modulo concept car, was tasked with the design and build of the Sigma. It was his first and only 'racing' experience.

Pininfarina was essentially given a Tamiya model kit and told to build an F1 car

"I had never seen an F1 race before," says Martin. "I invented everything. For me, it was a real test to perform at their best in which personal and company pride was at stake."

Martin disputes any claims of help with the project outside of Teo Page, tasked with putting together Martin's designs, but the project was overseen by Sergio Pininfarina, Revue Automobile's Robert Braunschweig and journalist/racing driver Paul Frere, as well as Dr Ernst Fiala from Berlin's Polytechnic University.

"This team started working on the Ferrari base in 1968 and they made a safety concept car, the Sigma," explains Sergio's son, Paolo. "It comes from the 'S', the Greek S, for safety."

The origin of the car's name is one of the simpler facts to determine in a story that's never fully been told outside of Martin's own book - which is only one, contested, viewpoint. But what is clear is that Pininfarina's innovation, at that period, was well in advance of its time.

"[With] the features of the Sigma Grand Prix, I counted five important things," says Pininfarina. "Actually, I'm not sure if all these things were really put 100% in F1."

Some of its ideas, consigned to history, were clever. The Sigma's bright green-and-white livery was fluorescent to help rivals see it in low visibility, an idea not picked up by F1. And there was a rear light to help identify cars in the fog.

But the key advance, particularly in the context of the 1960s, was the system to contain the spread of fire. Graviner, an English engineering company that specialised in such systems for aviation and nautical applications, developed a process using sprinklers that reacted to crashes and included warning lights for the driver if a fire started.

Combined with bodywork that allowed for greater absorption and dissipation of energy in a crash, it was a remarkable upgrade on the flimsy contemporary F1 cars that prioritised performance over safety. The Sigma even included a 'survival space', an early attempt at the now standard survival cell.

"What was most important was the side-impact absorption with energy dissipation and fuel tanks [that were] self-extinguishing; this was the most important item because it is why Bandini died," explains Pininfarina. "The tanks were separated by the body, they were not near the frame, but separated in space to absorb the shock. This was an improvement, I don't think the real F1 cars adopted 100% this patent, but they were modified following that direction.

"Niki Lauda's accident (pictured below) was on August 1 1976, seven years later [from the Sigma's birth], again in a fire. The fuel tanks [of the '70s] were not so safe, but safer than the '60s."

The Sigma's focus was certainly fixed on ensuring that crashes did not escalate, but it also included a rear wing that married Pininfarina's obsession with "lines" and aerodynamics with the goal of stopping an F1 car from rolling over and trapping its occupant. Nineteen years before road cars were mandated to use seatbelts in Italy, the Sigma had a seven-point safety harness to minimise injuries in a crash.

Martin believes that several features were adopted in motorsport as a consequence in the 1970s: "The idea of the safety with the helmet [the Sigma's harness included better protection for a driver's head], the external tanks and the fire-fighting system were used."

Those "five important things" that Pininfarina mentioned were not the only part of the Sigma's legacy. The design boss says the car was discussed by drivers in period (Pininfarina spoke to Emerson Fittipaldi when the pair met last year to discuss a hypercar collaboration bearing the two-time F1 world champion's name).

"The car is very close to being able to run. The project is solid and the powertrain and the electronics are not so complicated. With a good mechanic who knows F1 of the 1970s, I think it could run. The car is more of a space object on four wheels" Paolo Pininfarina

"It [the Sigma] was a strong effort by a group of competent people, and it very much got the attention of the drivers," says Pininfarina. "There was a safety campaign led by Jackie Stewart, there was a safety committee with the drivers. I know this as I met Emerson Fittipaldi in person, he told me the [Sigma] is fantastic and that they remember the project.

"They had considered it very much because there was a lot of sentiment and sensibility about the safety issue, and so they made the committee about safety, because F1 in the 1960s and early '70s was really unsafe."

The Sigma being talked about in drivers' meetings was about as close as Pininfarina would get to an F1 track, outside of the company's name being emblazoned on the skirts of Niki Lauda's Ferrari between 1975 and '77, as it was not even remotely close to contemporary F1 regulations.

"It was absolutely not legal, being out of all the regulations of the time," confirms Martin. It's one of the few things all of the Sigma's key players agree on, along with one lingering regret...

"I regret a little bit that the car is very close to [being able to] run," adds Pininfarina. "The project is solid and the powertrain and the electronics are not so complicated, so even to a good mechanic who knows F1 of the 1970s, I think it could run. It is possible.

"The car is more of a space object on four wheels; that's more linked to the Ferrari team, it's got the engine, the chassis and so on."

Martin says: "The Sigma has never been driven. Ferrari was not interested in the project."

Instead, it has lived in the museum as a byproduct of another age, as Pininfarina moved its attention to assisting Ferrari's F1 programme in the 1970s. The company is proud of its small role in Lauda's titles, after Pininfarina and Ferrari personnel worked together in the company's windtunnel in Turin.

As far as Pininfarina himself is concerned, the car has a legacy in the modern era: the company's new hydrogen-powered racing car, the H2, which it hopes will inspire the next chapter of motorsport.

"We took some inspiration with the H2, which is a completely different story," he says. "We took inspiration for racing of the future, that is new and very advanced.

"We made it in white, with the same colour as the Sigma to celebrate at the Geneva Show and celebrate the collaboration with our Swiss friends at Revue Automobile in the 1960s.

"I think the [Sigma] will become more popular in the future. It's a very intelligent car and a positive for the future. The world changes all the time, but it is important to remember that Pininfarina has always been attracted by the work of racing. The Sigma Grand Prix is a maestro in the story of racing."

Shame, then, that so few will see it tucked away among a collection of road cars, and even fewer know its story.

Sign in or subscribe

Sign in or subscribe Highlights

Highlights Series

Series Explore

Explore