Apur Sansar: Satyajit Ray's famed Apu Trilogy ends with a fascinating study of love and loss

Editor's note: In a prolific career spanning nearly four decades, Satyajit Ray directed 36 films, including feature films, documentaries and shorts. His films have received worldwide critical acclaim and won him several awards, honours and recognition — both in India and elsewhere. In this column starting 25 June 2017, we discuss and dissect the films of Satyajit Ray (whose 96th birth anniversary was in May 2017), in a bid to understand what really makes him one of the greatest filmmakers of the 20th century.

Satyajit Ray’s fascination with Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s immortal creation Apu lasted across three films, collectively known in the world of cinema as the Apu trilogy. For the final film in the trilogy, Ray focused on the life and experiences of a grown-up Apu. In it, through the journey of one young man, he portrayed the cyclical nature of human existence, and of such universal emotions as happiness and grief, of love and loss and of denial and acceptance, as they keep shaping our lives in turn. This film, which Ray made in 1959, after two successful attempts at making ‘popular’ cinema in between, was Apur Sansar (The World of Apu).

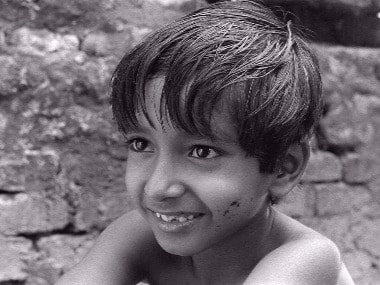

When the film begins, we see Apu as a handsome young man with dreamy eyes and empty pockets. He doesn’t have money to pay his rent, so he knocks the doors of every prospective employer in Kolkata, and yet fails to secure a job. But Apu hasn’t lost hope. On the contrary, he dreams of writing a novel someday, has literary ambitions, but is too lazy and careless to pursue those dreams. His laidback existence is financed by the private tuition he gives, but with not enough money coming in, he knows he has to look for a full-time job. This bothers him, because he either finds himself overqualified for available jobs, or under-qualified for the jobs he wants. Under such circumstances, one day, his old friend Pulu pays him a visit, to invite him to his cousin Aparna’s wedding in a village in Khulna.

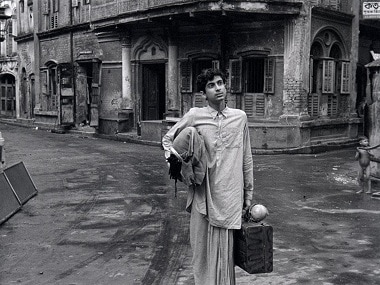

Apur Sansar marks the debut of both Soumitra Chattopadhyay and Sharmila Tagore, as Apu and Aparna respectively

On the day of the wedding, however, the bride’s family realises, much to their horror, that the groom has a serious mental disorder, and that he often turns violent. While Aparna’s father still wants to marry off his daughter to the groom, it is her mother who puts her foot down and calls off the alliance. A shroud of gloom descends upon the village, since in accordance to the traditional beliefs of those days, Aparna is about to miss the announced auspicious hour of the wedding, and would thus be cursed for life. To avoid such a tragedy, Pulu begs Apu to accept his cousin’s hand in marriage. Apu flatly refuses at first, but on realising that the entire village’s hopes are pinned on him, he agrees to marry the girl he hasn’t even seen.

Apu brings Aparna home, in Kolkata, and despite being raised in an affluent household, Aparna takes to a life of modest means and domesticity quite easily. Apu is worried because he has no job, but like a true companion for life, Aparna assures him that everything will be alright — without ever saying so in as many words. She is the perfect wife that a man can hope to be blessed with, and to her, her husband’s happiness and well-being is of paramount importance. Apu leads a content life of domestic bliss with Aparna, and she soon becomes pregnant. The couple are happy beyond measure, but this happiness doesn’t last for long. While delivering her child, Aparna passes away.

Apu is broken and shattered, and unable to accept the death of Aparna, he leaves the city and wanders through the length and breadth of the country. Back in the village, his son Kajol is growing up almost like an orphan, but Apu refuses to return to the village, because in his mind, he blames his son for the death of the wife he loved so much. In the end, however, weary and exhausted, he returns to the village, and on seeing his son for the first time, he realises his mistake. He accepts his son with open arms and finds peace and closure. The father and son walk away, to a new beginning.

While its predecessors Pather Panchali and Aparajito were praised for their rich aesthetics and deep humanism, Apur Sansar has been lauded all over the world for its fascinating study of love and loss. Two different scenes in the film, both involving Apu, highlight these two emotions in two contrasting manners, and yet both of them are so natural and visually stunning that they might well be considered amongst the best scenes ever written and shot by Ray. The first is a scene from the morning after Apu has brought Aparna home. The night has passed, and unable to show lovemaking between the couple to a largely traditional family audience, Ray shows the romance between Apu and Aparna through a series of shots subtly suggestive of what has passed. As the beautiful Aparna — the vermillion dot on her forehead now slightly smudged — tries to leave the bed, she finds the free end of her sari tied in a knot to Apu’s clothes. As Aparna frees herself, slaps her husband’s back as punishment for such mischief and begins her morning chores, Apu watches her from bed, stumbling upon one of her hairpins under his pillow. His face is filled with the fond remembrance of the previous night, and with a content smile on his face, he opens a packet of cigarettes to find a small handwritten note inside that says — ‘Only one. After meals. You promised.’ No amount of depiction of sex or lovemaking could have created such a beautiful suggestion of romance as this one sequence does.

With Apur Sansar, Satyajit Ray brought his Apu trilogy to an end. Several critics around the world consider it to be among his best films

The second scene shows Apu returning from work one day, reading his wife’s letter from the village on the way, only to reach home and find her brother waiting for him with the news of her death. In a state of indescribable grief, disbelief, shock and sheer rage, the otherwise mild-mannered and sensitive Apu clenches his teeth and punches the bearer of the news across the face — a sudden surge of uncontrollable emotion so beautifully understood by Ray and portrayed by his leading man Soumitra Chattopadhyay that it aches one’s heart just to think about it. It is moments like these that make Apur Sansar the film we all know. And the entire length of the film is full of such moments. Watch out for the expression on the face of Aparna’s mother when she threatens to kill herself if her daughter is forced to marry a madman. Or the fleeting moment of sadness on Apu’s face when Aparna’s mother blesses him with a long life — a moment when he perhaps remembers his own mother. Or the look on Apu’s face as he describes the plot of his novel to his friend, and Ravi Shankar’s haunting flute theme from Pather Panchali slowly rises in the background, as we begin to realise that Apu’s novel is more autobiographical than he is himself willing to accept.

But perhaps the best scene in the film comes towards the end, when Apu meets his son Kajol for the first time. In an instant, his misgivings towards the child are wiped out, washed away in his own tears, as he asks himself — how can something so beautiful and so innocent be the cause of my beloved’s death? He embraces his son, and hoists him up on his shoulders, and for the first time since the beginning of the film, we see the twinkle of joy in Apu’s eyes — the same twinkle that we had seen when he was a child in Pather Panchali.

Apur Sansar marks the debut of both Soumitra Chattopadhyay and Sharmila Tagore, as Apu and Aparna respectively, both of whom went on to appear in a number of films by Ray, and who, outside the filmography of Ray, went on to make their mark in the Bengali and Hindi film industries respectively. Their first film performance together, however, was perhaps their individual career bests.

With Apur Sansar, Satyajit Ray brought his Apu trilogy to an end. Several critics around the world consider it to be among his best films. It is also the film that sealed his position as a filmmaker who despite his fresh and ground-breaking ideas of cinema, had a steady finger on his audience’s pulse.

Bhaskar Chattopadhyay is an author and translator. His translations include 14: Stories That Inspired Satyajit Ray, and his original works include the mystery novels Patang, Penumbra and Here Falls The Shadow.

Published Date: Mar 11, 2018 12:24 PM | Updated Date: Mar 11, 2018 12:24 PM