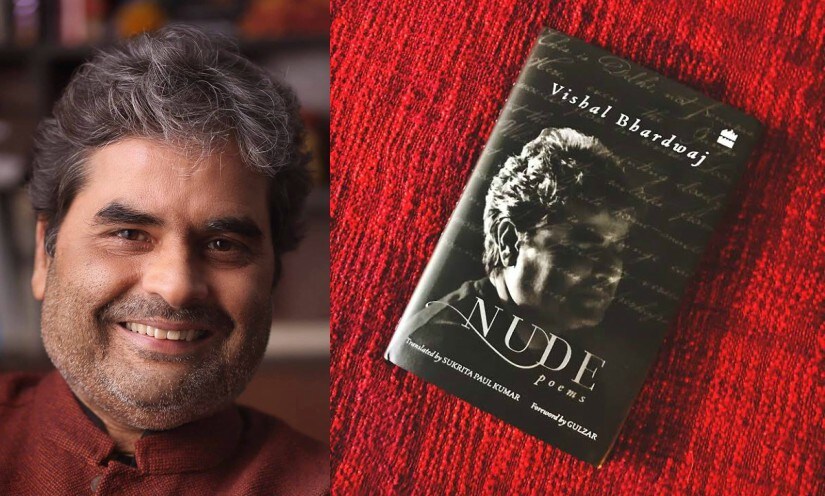

Filmmaker Vishal Bhardwaj has come out with a book of his poetry – his first. The book is aptly titled 'Nude’, for that’s what the poet does – he bares his soul to us through his poetry.

Ever since he broke out with Maqbool, his gritty adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth set in the throes of power struggle in the Mumbai underworld, Vishal Bhardwaj has come to be known as a filmmaker par excellence. His films are known to stand out within the space of so-called commercial Hindi cinema, and although they appeal to your average viewer, they can under no circumstances be branded pedestrian. His writing is excellent, his visual themes poetic, and as Anurag Kashyap once remarked, his grasp on dialects and diction is something that every filmmaker in this country should take a lesson from.

Although known primarily as a filmmaker, Bhardwaj himself has admitted that his first passion has always been music and that he started making films so that he could employ himself as a music director. Both music and poetry were in his blood – his father, the late Ram Bhardwaj, was a poet, musician and lyricist for Hindi film songs. From a very early age, Vishal Bhardwaj had been exposed to the works of Urdu poets such as Dr Bashir Badr and Gulzar, and he was hugely influenced by them. This is vividly evident in his own poetry as well.

The simplicity of Vishal Bhardwaj's verses in Nude is juxtaposed with the depth of the meaning they convey

Bhardwaj’s book of poems is divided into ghazals and nazms – the two most popular forms of Urdu poetry. Each ghazal and each nazm has been translated into English by Sukrita Paul Kumar. Bhardwaj’s poetry is lyrical and free-flowing, the words carefully chosen – pregnant with meaning, but never too heavy for their own good. He makes his verse ride on rhythm when required, but is cautious enough to dismount when he feels it would become a burden. Another oft appearing trait of his poetry is the objectification of intangible things – a feature that tends to highlight the poetry of his mentor and good friend Gulzar as well. Consider the following lines, for instance –

Din ka bhaari truck to mere seene se hokar guzraa,

Shab ki khamoshi bhi aakhir kuchal ke mujhko guzar gayi[The day’s loaded truck has already passed over my heart

The silence of the night too crushed me as it went by]

The salience of any good poetry is the simplicity of its verses as juxtaposed with the depth of the meaning they convey. By that parameter, Bhardwaj’s poetry fares quite well. Consider the simple simile hidden in these lines, in the context of the beautiful comparison it attempts to make –

Bachpan mein school ki jab

Bin kaaran chhutti ho to

Maare khushi ke bacchon mein

Kitna hulla hota haiBilkul waisa shor-o-gul

Mere andar hota hai

Jab milte ho achanak tum

Aate jaate raaston par[When for no reason

A holiday is declared at school

Jubilant are the children

What a din they createThat same hullabaloo

Rises within me

When out of the blue on some road

I run into you]

The book has 25 ghazals and an equal number of nazms – and they are fine examples of a richly visual and melodiously acoustic journey into the poet’s mind. He is able to share, with no difficulty at all, his feelings about a vast range of subjects – love, loss, grief, joy, life, death, the beauty of nature, the contentment in little moments of joy and even going to the extent of making strong yet valid comments on the socio-political situation of the country. If there is one thing that somewhat tends to mar the joy of reading the book, it has to be the translations. Some of the greatest poets of the world have failed while translating good poetry. In fact, the better the poetry, the more difficult it is to convey the emotion behind it in another language. Vishal Bhardwaj’s Nude, as a matter of fact, is best enjoyed in the language it was originally written in. However, this does not mean that if one does not understand said language, one should not read the book – it’s just that reading the translation would be akin to biting into a fruit that is less juicy than what it could have been.

This review has to be ended citing one of the nazms towards the end of the book, but before we plunge into the depths of the nazm, let us first refer to a few lines from an interview that the poet had given to Rakesh Anand Bakshi, in the latter’s book Director’s Diaries, first published three years ago. These are Vishal Bhardwaj’s words from the interview –

"On 7 May 1985, the date is etched in my memory, at Meerut while I was still in College, I returned home in the morning after Cricket practice, and saw all our family’s belongings spread out on the street. And my father lying on the street gasping for breath. The house we were living in was rented, and the landlord had obtained a seizure of property order to force us to vacate the house overnight, even though the matter had been settled out of court.

I held my father in my arms and amongst our belongings lying scattered on the street, we looked desperately for my father’s medicines, but could not find them. I went to get the doctor. When I returned, I realized my father had been shifted to a neighbour’s house. When I entered the house, it was too late."

I will now end this review with Bhardwaj's nazm titled ‘Toofan’ (Tempest) –

Ek aandhi thi aangan uda le gayi

Mera ghar-baar uss roz sadkon pe tha

Budha bargad ukhad ke zameen pe gira

Aur jadein uski aakash chhune lagi[A storm blew the courtyard away

My home and hearth lay on the roads that day

Uprooted, the old banyan tree fell to the ground

Its roots reaching for the sky above]

Published Date: Feb 08, 2018 19:59 PM | Updated Date: Feb 08, 2018 20:08 PM