Armed with his Walther PPK and a licence to kill, fictional British spy James Bond has dispatched countless villains over the years.

But it’s not only twisted masterminds and wicked henchmen he has sent packing with little more than a cheesy pun or two – his global box-office appeal grants 007 a level of soft power that has enabled him to carry out character assassinations of entire countries, too.

As the title hero in the longest running international blockbuster action franchise, Bond has spent decades traversing the globe on state-sanctioned assignments that capture the popular imagination and influence audiences’ impressions of the destinations and people he encounters.

All the while, Bond’s assignments are aimed at ensuring the physical safety, resource security, and geopolitical standing of Britain and its closest allies, most usually the United States. And while Bond frequently is set against megalomaniacs who lack official nationalities or affiliations, the reputations of other countries often become part of the collateral damage. This was most obvious during the Bond films’ treatment of the USSR during the cold war period – so concerned were the Soviets’ at their portrayal that they produced a novel directly pitting a Communist spy against the evil imperialist. Bond’s international influence remains to this day. It is not for nothing that Mexico reportedly offered Sony Pictures and MGM up to US$20 million in tax incentives to change the script of Spectre to cast the country in a positive light.

WATCH: James Bond – misogynism and China

Since the agent’s genesis in the febrile imagination of ex-naval officer and journalist Ian Fleming more than half a century ago, China has often found itself in the special agent’s cross hairs – even if this has been largely the work of film producers rather than Fleming himself.

China occupies an important place in the films, bookending the series, and its representation as a looming threat has in true Bond fashion influenced popular perceptions of the country’s role and position in the world.

Dear China, I am a white guy and not a spy

Fleming began writing spy novels in the early 1950s from his home in Jamaica. Bond, his most famous creation, was an amalgamation of characters he had known including his brother, Peter, and Bond’s globe-trotting was shaped profoundly by Fleming’s experiences of the world.

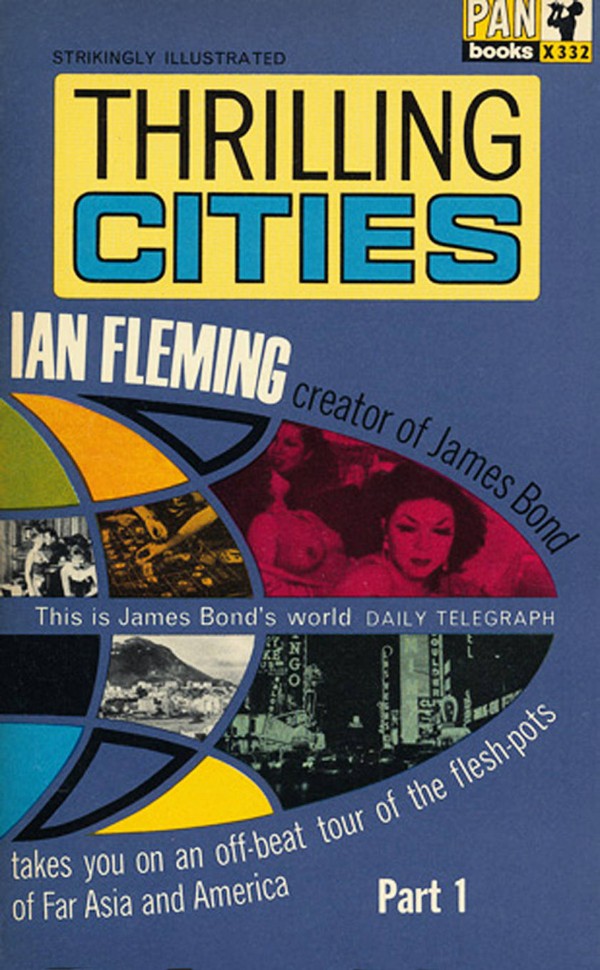

Fleming travelled during the second world war as part of his official duties for the British Admiralty and later, more extensively, as a journalist with The Sunday Times in London. In his 1959 book, Thrilling Cities, Fleming’s odyssey took him across North America, the Middle East and Asia.

Fleming found Hong Kong and Macau beguiling. He revelled in their “Oriental mystique”, and as British and Portuguese colonies he found his privileged position as a white British male gave him widespread access to glittery hotels and colonial clubs. Guided by a fellow journalist, Fleming learned about how Hong Kong’s criminal gangs, Macau’s gambling economy, and transnational smuggling had shaped these enclaves. Fleming wrote about the looming presence of the “communist frontier” in Thrilling Cities. Although he did not dwell on Sino-British relations, these were tense in the late 1940s and early 1950s as British and Chinese troops confronted one another on the Korean peninsula.

Spies and a magic weapon: why are Australia, NZ so suspicious of China?

Paradoxically, Fleming’s Bond novels have little to offer on the British-Sino relationship. Any reference to China in the Bond films is the product of the geopolitical imagination of screenplay writers such as Richard Maibaum and set designer Ken Adam. Both China and Russia, by the time of Dr No’s release in October 1962, were global geopolitical powers.

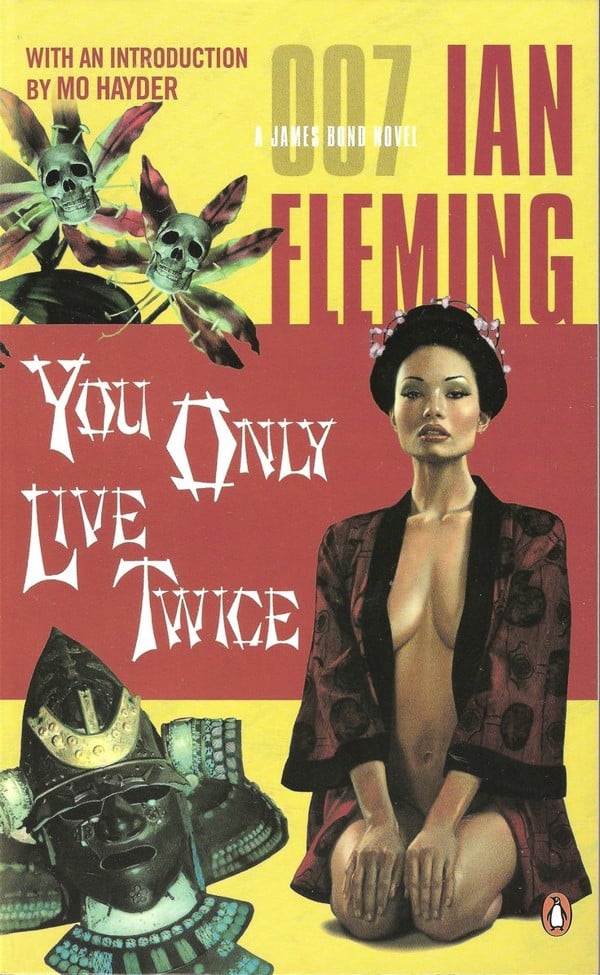

In 1967’s You Only Live Twice, China was presented as a nefarious force supplying dirty bombs, dirty scientists and dirty tricks to aid the evil organisation Spectre in its pursuit of global domination.

Tapping into the “yellow peril” – the xenophobic fear that people from “the East” and especially China would invade and occupy the (white) West – Chinese characters like Dr No and Mr Ling (in Goldfinger, 1964) offered their tactical and scientific knowledge to aid in the development of weapons that would directly impact the US.

Both men were depicted in suits in the style of Mao Zedong to align their actions with the Chinese nation state.

Moreover, Dr No is not only disfigured but also the product of a mixed relationship involving a Chinese father and German mother. The film seems to offer a warning to viewers about the perils of mixed-race unions. Thus from the outset of the Bond franchise, China was presented as a dangerous and transnational threat to the West.

WATCH: Shanghai in Skyfall

On a few occasions, Chinese characters have played a more positive and constructive role. Both Lieutenant Hip in The Man with the Golden Gun (1974) and Wai Lin in Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) serve as allies to Bond and (re)affirm the relationship between Britain and Hong Kong/China while providing a justification for Bond’s interactions in the region. But unlike Dr No, they prove to be trustworthy and capable.

Wai Lin, played by Michelle Yeoh, is a more capable and competent agent with her own secret home base and gadgets worthy of Bond’s tech guru, Q. While the film tips its hat to Chinese spies and their advanced technology, Lin is only present for half of the film so as not to outshine Bond. The film ends with Bond saving and successfully wooing Lin, thus reaffirming the superiority of Britain (code: masculine) over China (code: feminine).

WATCH: Macau Casino in Skyfall

The films of this decade have shown a China re-emerging as a threat to the physical and technological security of Britain and the West, albeit at arm’s length.

In Skyfall (2012), the villain Raoul Silva was an MI6 agent who went rogue and was delivered to China as part of the 1997 handover of Hong Kong from British to Chinese rule.

This is his motivation for seeking revenge on MI6 and his former boss, M. To uncover this plot, Bond has to navigate his way through a Chinese underground casino (code: traditional) and a sleek high-rise glass encased building (code: hypermodern).

WATCH: James Bond returns to classic roots with Spectre

The depiction of techno-orientalism and specifically the hacking of MI6 in the film is an explicit reference to the cybercrimes China has been accused of perpetrating against Western countries. And yet, for the release of the film in China, these references were removed to meet censorship requirements.

The most recent films featuring Daniel Craig as Bond are decidedly reversionist as they look back on and arguably replicate the world view of the Connery era films in the 1960s. This has been despite Craig’s first outing as Bond – Casino Royale in 2006 – being the first Bond film to be approved for Chinese audiences. Given Bond 25 is now in the works, it will be interesting to see whether the film’s producers will be swayed by the increasing influence of the Chinese film market.

A more positive portrayal of the country and its people might justly reflect China’s growing stature on the international stage, though after a half-century of niggles, that might offer only a quantum of solace. ■