“I don’t think you can go around writing all these histories of Russia’s ‘influence’ on China’s revolution by writing about Chinese sitting studiously in some room reading Marx and then diligently going out and organising the workers.”

Elizabeth McGuire, speaking by phone from California’s East Bay, continues by saying that, for the full story, you need to consider the passion and personal involvement of real human beings, not merely politically orthodox cartoon heroism.

McGuire was employed as a Russia expert in both the business and academic worlds when she noticed that the European country’s patchy post-revolutionary progress – one step forwards, two steps back – was repeated in the missteps that followed the Communist takeover of China, 30 years later. The revolutions shared similarly timed and equally ill-conceived campaigns for rapid economic growth as well as destructive widespread purges. “But all the books that I found were about ‘Sino-Soviet relations’ – that kind of geopolitical orientation, clash of great dictators focus, and ideology like, ‘When was the first Marxist work published in Chinese?’

“And to me, none of that explained what I was seeing,” McGuire says.

Donald Trump’s plan to play Russia against China is a fool’s errand

The revolution-exporting Communist International, or Comintern, monitored revolutions worldwide, and its labyrinthine Moscow archives contain more documents than any historian could absorb in a lifetime.

McGuire spent more than a year with little-seen material covering Chinese students in Moscow, each of whom had a file. Here she discovered connections between the revolutions at a more personal level, in the experiences of Chinese who lived and studied in Russia from the 1920s.

In their letters and other records, the Sino-Soviet relationship was revealed to be far from the fraternal one described in official accounts; Chinese students learning revolution fell in love with Russians or with each other, married or lived together, sometimes in unconventional combinations, and produced children, whether in or out of wedlock.

“At first I thought I was writing a generalised social history,” McGuire says. “I wasn’t going to have protagonists and love stories. But when I was sitting there in the archive, what was most striking and that leapt out of pages and pages of basically ideological claptrap were these deeply human, raw documents talking about love and revolution. It was something I’d never seen or heard anywhere before.”

Neophyte revolutionaries were taught that the ideological struggle and love were opposites, but they often saw revolution as providing opportunities for love that had previously been denied.

“Now people,” wrote one frustrated student, “unless they no longer have their private parts, all have sexual desires and excitement as well as the painful hopes and desires of love. So love is an uncontrollable element in the lives of people, and unhappiness in sex, although we can use all kinds of methods to lessen it, these are all just wilted flowers, unable to get results! […]

“Actually, love doesn’t jeopardise our studies in any serious way, on the contrary, it can increase our interest in studying. On the contrary, if appropriate concessions aren’t made to youthful sexual desire, and if sincere passion has no outlet, if there is no way to smooth and steady such urges, only then will we ‘worry’ and harm our studies!”

Paranoia from Soviet Union collapse haunts China’s Communist Party

While the archival free-for-all that had been made possible by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 was long over, McGuire found files that had been little scrutinised, and were left open to foreign researchers because of their dates.

“The Russians divide their Communist Party archive into two sections,” she explains – one for before the war and the death of Stalin, and one for afterwards. “And they’re not quite as concerned with what people do and don’t see from the period before the war.

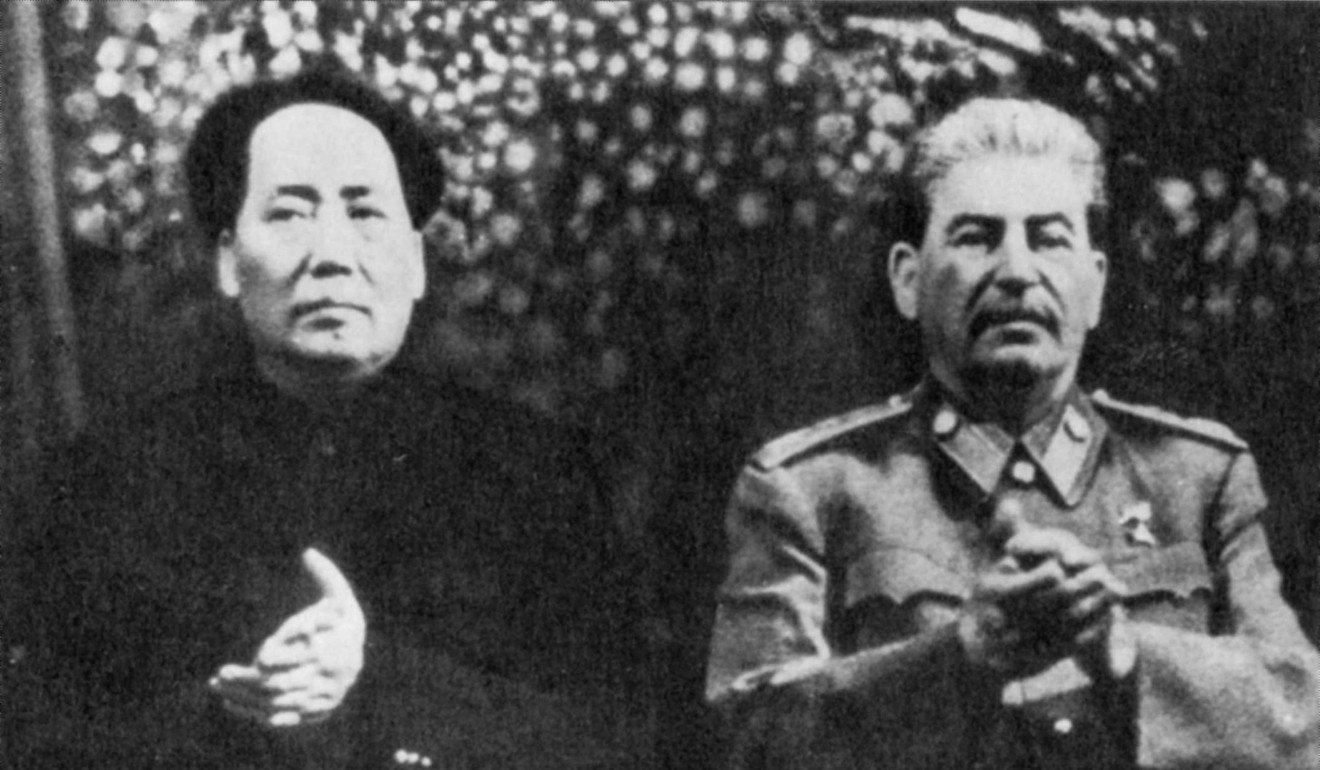

“They had folders and folders of letters”, and in these accounts of the revolutionary drama, Mao Zedong and Joseph Stalin play only walk-on parts.

Their revolutions may link them closely in modern eyes but in the 1920s, the two powers’ ignorance of each other was profound.

When China thought of Russia at all it considered its vast neighbour backward and corrupt, an enemy that had swallowed up parts of Manchuria in the northeast and Xinjiang in the northwest. But by the 1920s, the intellectual emancipation stutteringly and unevenly spearheaded by the New Culture Movement’s revolt against Confucianism and against inward-looking cultural tradition had sparked greater interest in learning foreign languages – although Russian was rarely among those chosen, and teaching rarely available. English predominated, and travel from China was mostly to western Europe, with many future Communist Party luminaries studying in France.

It took the Chinese general inspector of a railway to Vladivostok, desperate for staff able to comprehend agreements with Russia on the operation of the line, to found the Russian Language Institute, in Beijing. It had a dearth of dictionaries, it lacked much in the way of translations of Russian literature or teaching materials and only the fact that tuition was free secured it a body of students. Along with the language, they absorbed the ideas that would make some of them communists.

Eventually, a handful of Russian-language schools funnelled candidates of promising fervour to the Soviet Union for indoctrination in revolution. But those who reached the Communist University of the Toilers of the East, in Moscow, found it similarly lacking in teaching materials and qualified staff. They also faced struggles with political jargon and acronyms for which a limited knowledge of Turgenev and Tolstoy left them ill-prepared.

Anti-Soviet genesis of Cultural Revolution set stage for Chinese diplomatic revival

But as the western European revolutions predicted by Marxist theory failed to appear, and as the numbers of Chinese arriving to study in Russia grew, so did Soviet enchantment with China as fertile ground for fresh communist gains, although initially most Soviet funding and support went not to the fledgling Chinese Communist Party but to the far more numerous and better armed Nationalists.

Eventually the Chinese students were given their own Chinese University, where they received clothing packages and five meals a day, and remained largely unaware of the subsistence diets and threadbare apparel of most ordinary Russians.

What began as a trickle in the ’20s still represented a significant proportion of Chinese Communist Party membership at the time and by 1928, as much as 15 per cent of Politburo members had been educated in Russia. In total, up to the 1950s, 8,000 or more Chinese students passed through Russian revolutionary institutions, typically staying for about two years.

The students were mostly not “toilers” themselves, but descended from educated landed gentry or decayed minor aristocracy, or those with some link to high-ranking Nationalist or Communist leaders. Sent on summer breaks to the countryside to “implement communism”, they proved unused to manual labour and averse to chores, and had no understanding of rural life.

“There was a purge of Trotskyists and other suspicious Chinese elements in the late 1920s, and a bunch of Chinese students were sent out to these provincial Russian cities as a kind of light punishment,” McGuire says. “At least they weren’t shot, but they were sent to work in factories all alone or maybe with a couple of other Chinese, and they wrote these plaintive letters back to the Chinese leadership of Communist International, in Moscow.”

On the whole, interactions with ordinary Soviet citizens were limited, and often disenchanting when they happened, although some encounters with the opposite sex presented, as McGuire writes, “an exciting new way to practise Russian”.

Here, the young Jiang began a politically incorrect relationship with Feng Funeng, the daughter of Feng Yuxiang, a warlord who unreliably supported Nationalist attempts to reunify a China that had fragmented after the abdication of the last emperor, in 1912, and who would expel the emperor from the Forbidden City in 1924.

More ordinary figures included Chen Bilan, whose truly revolutionary approach included cutting her hair short and ditching an arranged marriage to board a train for Russia in 1923, becoming one of the first Chinese women to study there.

Comintern still aimed to export revolution through the indoctrination of males, and the women were mainly in Moscow as concessions, although it repeatedly decried how few they were, and its inability to recruit more.

Chen chose chastity, but female students with lovers back in China were under immense pressure from the male majority to drop them and find new partners. Even Feng Funeng was perpetually pestered, despite being openly paired with Jiang, and she criticised the promiscuity of her classmates.

“When they’re living together they inevitably have children. There’s already 12 who have given birth,” McGuire quotes her as saying. “The female comrades haven’t come here to study, they have simply come to have babies.”

The Chinese University contained a special room supposedly for the use of husbands and wives, but scandalously – even for those experimental times – it was, in fact, used for romantic liaisons by any interested couple, married or not.

Chinese revolutionaries returned to China to take up significant Party roles on the basis of the revolutionary credentials their time in Russia had earned them. Some took their new Russian or European spouse. Some didn’t take their offspring.

Sino-Soviet orphans were lodged at the International Children’s Home (Interdom), a few hundred kilometres outside Moscow, and would be joined by children dispatched for safety from Chinese Communist Party bases after the 1927 Nationalist massacre of Communists.

Not long after the declaration of the People’s Republic, in 1949, 32 Russian-speaking Chinese students were “returned” to a China many of them didn’t remember, some had never experienced, and for which all were largely unprepared. Many were eventually settled in a Russified Harbin, where they struggled to learn Chinese just as some of their parents had struggled to learn Russian.

In pictures: Russia marks 100th anniversary of Bolshevik Revolution

Already fluent in Russian, McGuire set about mastering Chinese to a level that would allow her to translate the letters she unearthed in the Moscow archive herself. She found a teacher in Beijing whose first foreign language was Russian, and who put together lesson plans based on vocabulary she drew from McGuire’s source documents.

In China, her sources were both published memoirs and personal interviews with ageing alumni of the Interdom children’s home who’d had to rediscover their Chinese heritage as teenagers or young adults.

Her discovery of the existence of Interdom itself had been accidental, from its mention in a Russian-language memoir by a Chinese woman whohad been a former resident. The school, now badly underfunded, remains a residential orphanage for Russian children and some from former Soviet republics.

On a whim, McGuire boarded a bus to the town of Ivanovo and, with some difficulty, located the school, out in the countryside. Officials at the school mentioned that a reunion was planned for the following year, so she just appeared at that and wandered round looking for Chinese faces.

“Anyone who looked Asian I’d say, in Russian, ‘Hey! My name is Lisa. I’m an American. Are you Chinese?’ It was pretty comical. It was frightening. I’d never done anything like that before. I was so curious and determined.”

No one quite believed she was American, because what kind of American would care about that kind of story in that kind of place? She begged for phone numbers and invitations, but, once in Beijing, she found the former Interdom students reluctant to open up.

“I’d have to visit several times with no particular questions before I could bring out the tape recorder,” she says. “Some of their parents had been victims of the Stalin purges only to die in the Cultural Revolution. There were stories that were so sad.”

The hunt for Red October: how the Bolshevik Revolution turned into a Chinese tourist trap

Having lived through political upheavals in both Russia and China, her returnees had learned that what might be acceptable to say today could condemn you tomorrow.

“There was a period of time,” McGuire says, “when they thought, ‘Wait a minute. Who have we been telling our life stories to? What kind of an American is this? She’s got to be a spy.’”

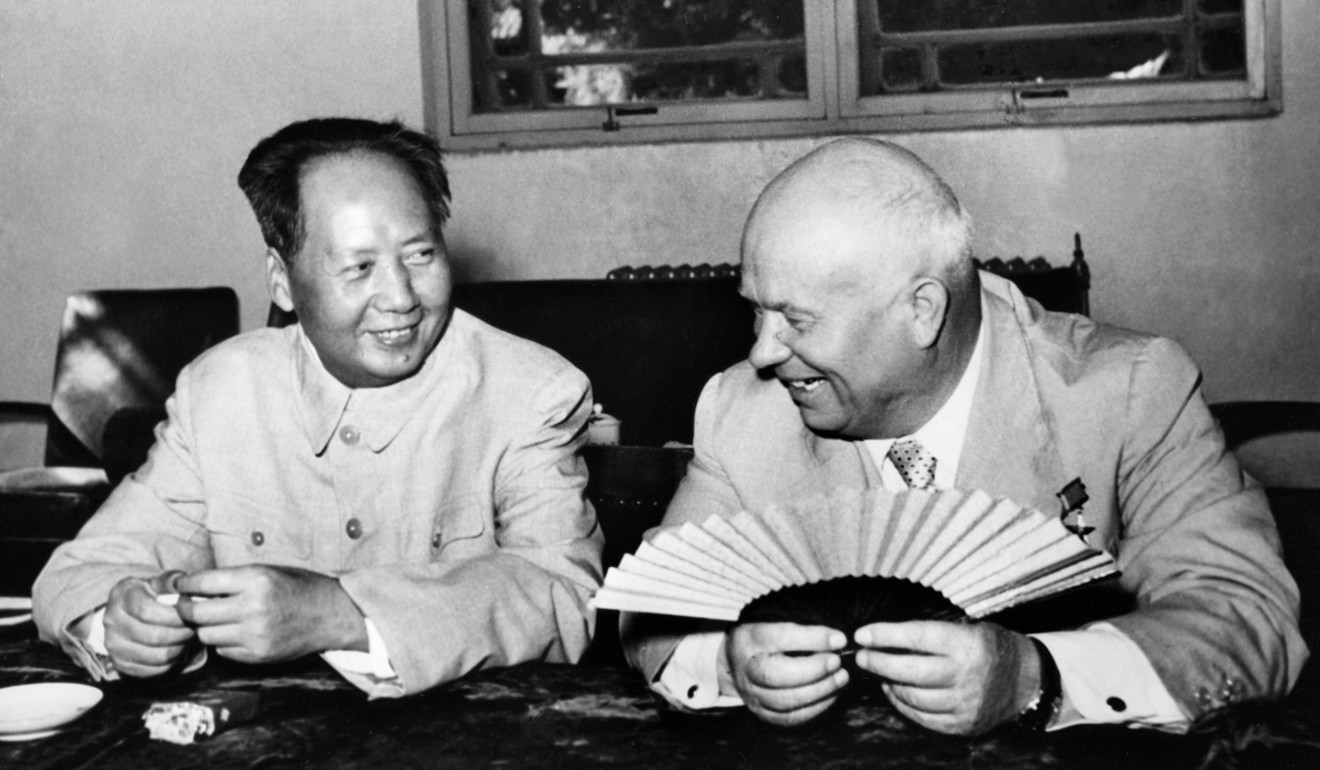

McGuire’s chapter on the returnees’ struggle to adapt is made still more poignant by the reader’s knowledge that Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin and China’s subsequent suspicion of all things Russian is just ahead, to be immediately followed by the comprehensively xenophobic Cultural Revolution. Many Russian wives felt forced to leave China, and some Chinese husbands demanded divorce on the basis of the innate political unreliability of their imported wives.

How Mao and Khrushchev fought over China-India border dispute

But many of the graduates had themselves become parts of and party to the apparatus of oppression. Even those who had seen Stalin’s purges first-hand said little about those experiences in public. Did they actually deserve sympathy?

“If you look at the Russian revolution as a whole, what a disaster,” McGuire says. “So many people died in famines and purges and wars and in the civil war. It was a brutal process.”

Part of what motivated her to spend years on research was that in the ’20s, a significant proportion of the tiny Chinese Communist Party would have been in Russia at any one time, and they witnessed the famine and the purges.

One of her subjects, the Chinese poet who came to be known as Emi Siao (who had a Russian wife and then a German wife, followed by a Chinese wife before remarrying the German wife) travelled through the Russian countryside experiencing desperate famine, yet failed to write a word about it.

“What was so fascinating to me was that they knew what had happened in Russia and yet they [went through with the Chinese Communist revolution] anyway. And why did they do it anyway? I kept trying to figure that out, and I could never satisfactorily answer it except that I think that they maybe thought, ‘Well, we’ve seen what happened in Russia and that doesn’t have to happen here.’ Maybe they thought that was an excess that didn’t need to occur.”

She sees the returnees as part of the reason the Chinese revolution repeated the mistakes of the Russian one, but a full explanation of their motives remains elusive.

“I was trying to write something which had not yet been written, a story about these people with certain desires and assumptions and world views, how they step-by-step happened into or made happen or helped to make happen something so tragic. Because to me they couldn’t have started out to say, ‘OK, now I’m going to dedicate my life to killing millions of people.’ They had to have thought something else and had to have gone step by step.”

In Red at Heart, McGuire is attempting to inhabit their worlds and understand their motivations. What was her PhD thesis has been turned into a readable and often engaging account, with a fresh angle on familiar events and full of small surprises – such as that lower-level Interdom staff included He Zizhen and Zhang Mei, the cast-off wives of Mao and his later second-in-command, Lin Biao, respectively, both of whom worked as nannies. And that He was eventually confined to an asylum, although it remains unconfirmed whether Mao knew it or not.

Russia and China remain inextricably bound together, McGuire feels, and that’s in part a legacy of the personal relationships of the ’20s and later. The Chinese Communist Party still fearfully studies the Soviet Union’s collapse to avoid emulating that event and, to some degree, it measures its progress against developments in Russia.

“In my lifetime, Russia will continue to be some part of China’s identity,” McGuire says, “positive or negative, in a way it never was before the revolutions and that it never could have been without the human emotional engagement first, on an individual level, in the ’20s and ’30s.”