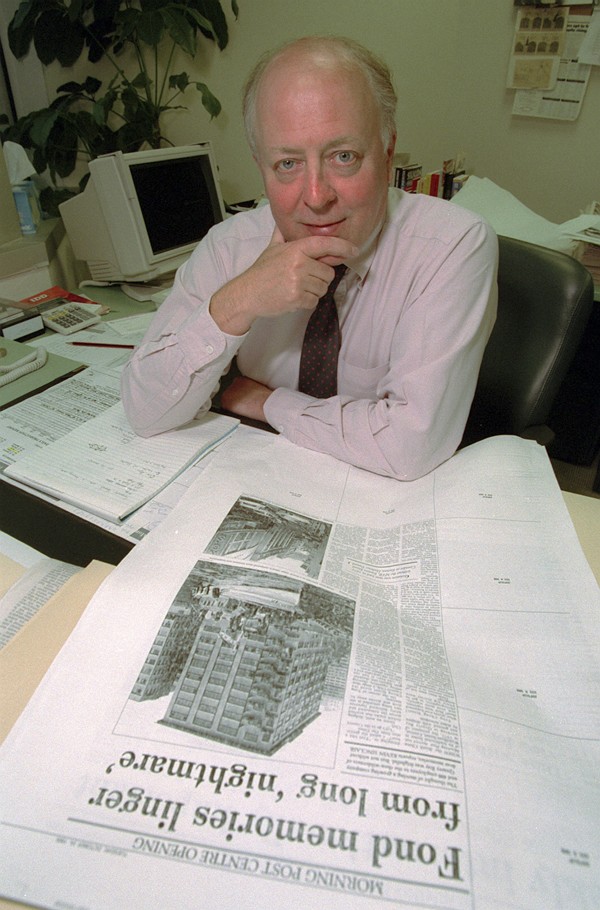

One Thursday afternoon in January 1995, Jonathan Fenby, then the editor of The Observer, a British Sunday newspaper, lost his job. Eighteen months earlier, to

the delight of its journalists, The Observer had been taken over by The Guardian, a left-wing daily newspaper. The idea was that both papers would continue to operate separately under the benevolent proprietorship of the Scott Trust –

what you might call the one owner, two systems principle.

It didn’t work out. From a certain angle, it sounds curiously prescient. Political coverage and commentary in The Observer was criticised from on high. Guardian writers were inclined to view their newly enfolded, formerly cosseted compatriots as “a bunch of dilettantes”. And, as Fenby put it later, “the foreign desk told joint stringers that their first loyalty was to the daily”.

When it came, his termination was swift and couched in doublespeak. Fenby was told that, as the Scott Trust couldn’t be seen to sack an editor, he was resigning. He was then instructed to leave the building immediately. As a concession, he was permitted to speak, briefly, to his deputy.

The following evening, he received a call from Andrew Knight, his editor at The Economist when he had worked there in the 1980s. Knight told him that the South China Morning Post was looking for a new editor. The timing was perfect; not only was Fenby available, he was of the required nationality. The Kuok family, who owned a controlling interest in the paper, specifically wanted a British editor. (The Equal Opportunities Commission wouldn’t be established in Hong Kong until the following year.)

The following evening, he received a call from Andrew Knight, his editor at The Economist when he had worked there in the 1980s. Knight told him that the South China Morning Post was looking for a new editor. The timing was perfect; not only was Fenby available, he was of the required nationality. The Kuok family, who owned a controlling interest in the paper, specifically wanted a British editor. (The Equal Opportunities Commission wouldn’t be established in Hong Kong until the following year.)

So, a few months later, despite his own protestations of ignorance about both the colony and China, Fenby came to Hong Kong. The day after he landed, he was told that the Sunday Morning Post and South China Morning Post – again, two separate editorial entities – were going to merge. Any sense of déjà vu he might have felt was tweaked by the realisation that culling certain staff on this side of the globe had political implications.

Meanwhile, another merger was about to take place, beyond the Post’s Quarry Bay windows. As you might expect, Fenby had arrived in pre-1997 Hong Kong with a plan to write a book analysing a place on the cusp of great change. The place in question, however, was France. He worked on this throughout much of his editorship.

In January 1999, Fenby was told that his contract in Hong Kong wasn’t going to be renewed, and he left the newspaper in July (although he returned that autumn for a few editing stints). He remained in Hong Kong until the end of the year to write a book, in the form of a journal, called Dealing With the Dragon: A Year in the New Hong Kong (2000). In it, he compares the people of Hong Kong (“invigoratingly upfront, smart and anxious to get on with life”) to Parisians, which perhaps suggests that his mind hadn’t strayed too far from France.

Fenby was back in Hong Kong recently. He returns several times a year for his work with Trusted Sources, which he co-founded and which provides investment research on emerging markets. On this occasion, however, he was giving two talks at the Hong Kong International Literary Festival – one on France, one on China, having now become an acknowledged expert on both. His most recent book on the country is his eighth on the Middle Kingdom. It’s called Will China Dominate the 21st Century? (2014). (Spoiler alert: chapter five is titled “Why China Will Not Dominate The 21st Century”.)

The afternoon we meet, in the BreeZe Lounge at the Lan Kwai Fong Hotel, in Central, is the eve of Fenby’s 75th birthday, as good a moment as any for recollections. Although I was a features writer on Post Magazine for 18 months during his editorship, I had met him only once, when a luxury brand had taken exception to a story I had written and withdrawn its advertising.

Fenby had appeared in the magazine office, looking as if he had more onerous tasks to worry about, and had mildly suggested that it might be helpful – from the advertising team’s point of view – to try to avoid a repeat.

As a young man, he was inexplicably convinced he would die at 40. There had been several near-misses.

During the London Blitz, his mother had moved to Essex but, in 1944, when Fenby was two, a German V2 rocket fell near the house, bringing down a ceiling; if his cot had not been placed under a table, the Kuok family would have had to look elsewhere for their British editor.

In 1965, covering the Vietnam war “as a boy correspondent” for Reuters, two American helicopters wouldn’t take him on a resupply mission; a third agreed. The first two didn’t make it. He also survived severe hepatitis in Vietnam, and Reuters was obliged to fly him back from Saigon, first class, on Air France. As he recalls, with amused regret: “Foie gras! Champagne! And I couldn’t touch them.”

War correspondent Clare Hollingworth, who has died aged 105, wasn’t going to say goodbye easily

But that bon viveur side saved his life in 1974, when, during a strike by British European Airways, he was booked on a Turkish Airlines flight from Paris to London, leaving at midday on a March Sunday. By then, he was married to Renée, whom he had met while based in Paris, and fancying a good lunch with his in-laws, he decided to delay and go early on Monday morning. Soon after take-off, Flight 981 crashed outside Orly Airport, killing all 346 people on board in what was then the worst accident in aviation history.

Fenby recounts these close shaves with proper wonderment. They have left him with a mixture of fatalism and superstition. When he starts to describe a bad motorway accident he survived in England, he murmurs, for a second, “I wonder if I should say this. I’m almost courting …” Yet on he continues, finally summarising: “Things happen. You don’t decide. I didn’t start out saying, ‘I want to be an editor.’ Maybe it’s a lack of strategic planning, but things evolve.”

Becoming a journalist “was the most unimaginative career path” for Fenby. His father, Charles, was a founding editor of the Oxford Mail, assistant editor of Picture Post and, ultimately, editorial director of a regional newspaper group, Westminster Press. His mother had been the writer Rebecca West’s secretary before becoming editor of a nursing magazine.

“She didn’t know the first thing about nursing,” says her son. (Not a family, clearly, to be daunted by fresh woods and pastures new.)

But Fenby’s progression through the media ranks seems to have become an increasingly grim trudge. “I was practically in a clinical depression at The Observer,” he admits. The desire to get on a plane out of London was finally realised after a chilly January walk and a poor Chinese meal. He and his wife decided to go “where the rain is soft and the Chinese food good”, which, ignoring subtropical downpours, is about right.

The entire episode is a textbook example of “Failed in London, Try Hong Kong”. While I’m working up the nerve to ask Fenby if this is how he views himself, I mention the overlap with the last governor, who had arrived, in 1992, also in a bruised professional state. (Chris Patten, as chairman of Britain’s Conservative Party, had led it to election victory but lost his seat as a member of parliament; Hong Kong was the consolation prize. As it happens, Patten was another Francophile, who took French lessons while he was here.)

“The first time I went to see him,” cries Fenby, instantly, and gleefully, getting the point, “I said to him, ‘We’re both FILTH!’ I don’t think he laughed.”

When I remark, however, that, judging by a re-read of Dealing With the Dragon – his take on the era – he wasn’t terribly happy at the Post, Fenby looks genuinely surprised.

“I probably put more things in that book ... You know how it is: bad news always takes precedence.” A little later, he says, “There were quite a lot of moments of tension, and I sent off angry faxes, but that wasn’t a sign of unhappiness. Perhaps I overegged it.”

So how happy was he? “I was 90 per cent happy, and my wife was 110 per cent happy,” Fenby says. “She really relished it, she was so happy this morning being [back in Hong Kong]. If I’m being self-regarding, it was the kind of newspaper, at that point, that suited me well.”

Meaning? “It was a big paper, it had a lot of good journalists operating on a very news-driven agenda, you had the whole China story starting to take off and also, you might say, it was the first time I’d written for a newspaper that made money.”

It was the Post’s advertising revenue that made it so famously lucrative. Apart from occasional withdrawals by outraged clients, the money poured in. “There was never any pulling of that rug,” Fenby says. “I was free to spend.” And he always had a painful benchmark against which he could measure his Hong Kong experience. As he writes, “What is surprising is that I was not fired much earlier, as certainly would have happened under a Western press baron.”

“Yes, yes, I must have sent it from an account of my wife’s,” Fenby groans, rapidly clicking the pen in his hand. “I know I shouldn’t. I’m terrible. Do you remember George Adams?” (I do – author of The Great Hong Kong Sex Novel [1994] and founder of the website Not The South China Morning Post.) “I made the terrible mistake of responding to him on several occasions.”

This brings to mind, as a study in temperamental contrasts, a moment Fenby recounts concerning his former boss. When Robert Kuok, owner of the Post until 2016, complains that the books written about him are full of lies, Fenby asks why he doesn’t issue a rebuttal. “[Kuok] laughed at the idea of revealing himself to the world in such a manner.” (Almost two decades later, Kuok has just written a 376-page memoir that’s fairly sparse on the personal-revelation front. Of the newspaper he writes, “When I read the Post in the morning, I wouldn’t agree with everything. But that had never prompted me to try and change its contents.”)

Does Fenby feel like a China expert? “I’m always wondering about this, about when you become an expert,” he replies. “There are a lot of people who have studied China – Chinese, Chinese literature, Chinese culture – in enormous depth. Twenty-four hours before I had my first conversation with the management of the Post, I’d no idea I’d be here.”

Does he speak Chinese? “Badly. That’s the thing ... and I don’t read Chinese,” he says, adding that he prefers to describe himself as someone who follows China rather than claim expert status (though, as he later remarks, the experts aren’t always expert either). “A number of very, very learned people will forecast what’s going to happen in China, because that’s the logical progression from a Western political, economic and social system. But, actually, China is different.”

Does he speak Chinese? “Badly. That’s the thing ... and I don’t read Chinese,” he says, adding that he prefers to describe himself as someone who follows China rather than claim expert status (though, as he later remarks, the experts aren’t always expert either). “A number of very, very learned people will forecast what’s going to happen in China, because that’s the logical progression from a Western political, economic and social system. But, actually, China is different.”

Indeed. Curiously, the Sino-track of Fenby’s literary career since leaving the Post seems to have been dictated by Western publishing trends.

“I don’t want to sound like a little toy duck that’s on the waves come what may, but there is an element of that,” he says.

‘I feel lost in Hong Kong’: why travel writer Paul Theroux finds the city ‘impenetrable’

Although he had arrived in Hong Kong with the intention of writing “a quickie” on France, his London agent soon told him that quickies were out of fashion and big tomes were in, so he spent considerable time in airports and hotels toiling over what eventually became On the Brink: The Trouble With France (1998).

By then, he had fallen out with the agent but he acquired a new one with the help of American writer Paul Theroux, who had spent a day at the Post offices writing a New Yorker piece on the handover. (“I said, ‘Mr Theroux, you’re a famous and respected author, I’ve got this book ...’”)

Once On the Brink was out, the publishers wanted a Hong Kong book.

“They thought it was going to be exciting, tanks on the streets,” Fenby recalls. “I said, it isn’t.” That became the post-handover Dealing With the Dragon. “Rather like a careers master at school, they said, ‘Well, young man, we think your next book should be a big biography.’”

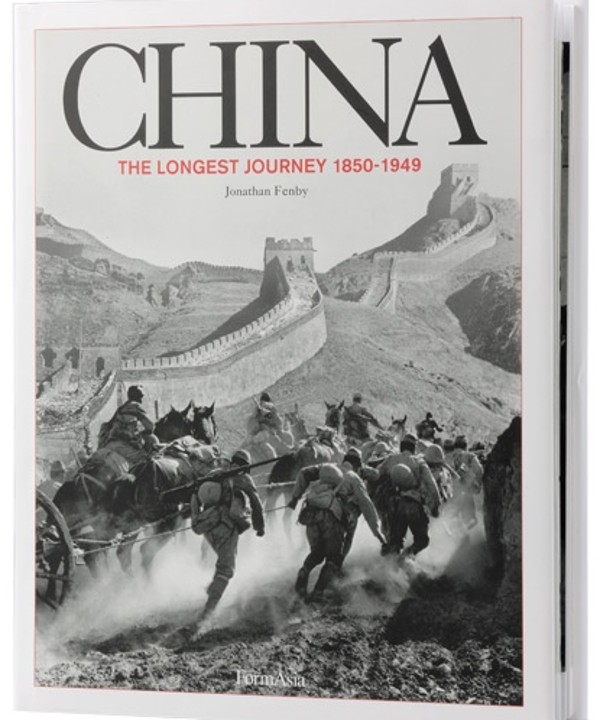

The titles of subsequent books (The Seventy Wonders of China [2007]; China: The Longest Journey 1850-1949 [2008]; The Dragon Throne – China’s Emperors From the Qin to the Manchu [2008]; The Penguin History of Modern China [2008]) chart his wavy voyage. The industry is extraordinary; during the same period, he also wrote, among other things, a biography of Charles de Gaulle and a history of modern France.

He has just completed Crucible, which will be published this year; it describes how the world changed between the beginning of June 1947 and the end of June 1948, and involves a cast of such complex characters as Joseph Stalin, Jawaharlal Nehru, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Harry S. Truman, Ho Chi Minh, Sukarno and David Ben-Gurion.

In a way, the Post was his crucible. In the 1990s, both he and the city underwent a transformation, courtesy of China. He seems to have got the better deal.

He was fluent and funny, with the journalist’s – rather than the academic’s – flair for a pull quote. (“The Chinese probably think the Russians are a bunch of drunks that are going to die off as a race”; “When I lived here, Martin Lee was ringing to have lunch at the Hong Kong Club – now it’s Joshua Wong on the barricades”.)

Fenby was, he admitted, apprehensive about his audience, and rightly so. From this side of the world, some of the West’s media coverage can look peculiarly skewed.

China’s rise is assured in our new world order, but not as a hegemon

“There is a bad-news story about China which does play,” he said, when it came up in questions afterwards. “But that doesn’t mean it’s not true.” To further observations about Western bias, he replied, “I wouldn’t say it’s wrong. But the system [in China] is hermetically sealed. There are no satisfactory answers.” (Which rather makes you wonder what everyone’s analysing.)

“It’s a far freer place, on an individual basis, than when I first went there in the 1990s,” he said, to a general murmur of agreement in the room. A little earlier, he’d remarked, “I don’t think China wants to dominate the world. It wants respect.”

Odd, in that case, that the word dominate should appear so prominently in his title; but that, he said when someone asked, was what the publishers had wanted.