The question had never been asked before, perhaps because it seemed preposterous; like asking Italians which pasta is the finest; or Germans which sausage best embodies the soul of the country; or Americans whether the peanut butter is more important than the jelly? And when it was asked, all hell broke loose.

What is India’s national dish? The furore developed because the upstart being discussed as the main contender was so outrageously ordinary. Adish eaten in almost every Indian home, khichdi is a mix of rice and lentils, cooked with spices and tempered with dollops of ghee (clarified butter) in its most rudimentary form.

An insider’s guide to Bangalore’s best places for vegetarian food

But, as you travel across the subcontinent, khichdi is prepared in an almost infinite number of permutations, some of which challenge the risotto in sophistication. It’s one of those peasant dishes, like the fava mudammas in the Middle East, that are so bursting with comforting flavours they’re difficult to tire of.

When French president Charles de Gaulle grumbled that it was hard to govern a country with 240 varieties of cheese, he had obviously never considered India. The meals a Muslim carnivore in northern Kashmir sits down to bear no resemblance to those eaten by a vegetarian Hindu Brahmin – not at the other end of the country but next door, in the neighbouring state of Punjab.

What’s more, the debate was triggered by a news story that turned out to be fake.

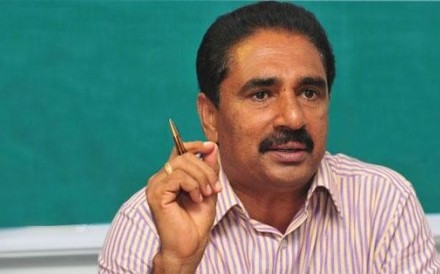

Harsimrat Kaur Badal, India’s minister of food processing, asked famous chef Sanjeev Kapoor to inaugurate the recent World Food India exhibition in the capital with 800kg (1,760lbs) of khichdi, to be cooked in a massive cauldron outside the venue.

Cookbook: Sanjeev Kapoor’s Mastering the Art of Indian Cooking

In media coverage, Badal happened to call khichdi “the wonder staple food of India” and said it symbolised “India’s great culture of unity in diversity”. Before Kapoor’s cauldron had even come to the boil, word had spread that Badal had declared khichdi to be India’s national dish.

The story flew far and wide because Indians rather like their “national” objects. The country’s national tree is the banyan; national fruit the mango; national bird the peacock; national animal the tiger; national river the Ganges; and national flower the lotus.

Although Badal quickly clarified that she had no such grandiose ambitions for khichdi, the report convulsed the nation, the dish being either reviled as fit only for invalids and infants or revered as the ultimate comfort food. Debates had begun, involving weighty matters such as whether India’s ancient civilisation could be defined by any one dish or whether any attempt to do so was a venture worthy only of a village idiot.

“Do we now have to stand and sing the national anthem every time we have khichdi?” some asked, with tongue placed firmly in cheek, one hopes.

If looks were the sole criterion of a national dish, khichdi would fail miserably. After diced vegetables are added to the gloopy rice and lentil mixture, the result is of a porridge-like consistency and is a mushy mess (no dentures required, therefore ideal for the elderly and infirm). But if universality and antiquity were the criteria, it would pass with flying colours.

How to get to know India through its food: an insider’s guide to some must-try experiences

The 3,000-year-old Hindu religious texts, the Vedas, mention a form of khichdi. Foreign travellers wrote of it in their chronicles. In 290BC, Greek historian and diplomat Megasthenes observed that a combination of rice and pulses was a common dish across India. In the 14th century, Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta also noted the popularity of the dish.

“This is what they call kishri, and on this, they breakfast every day,” Battuta wrote.

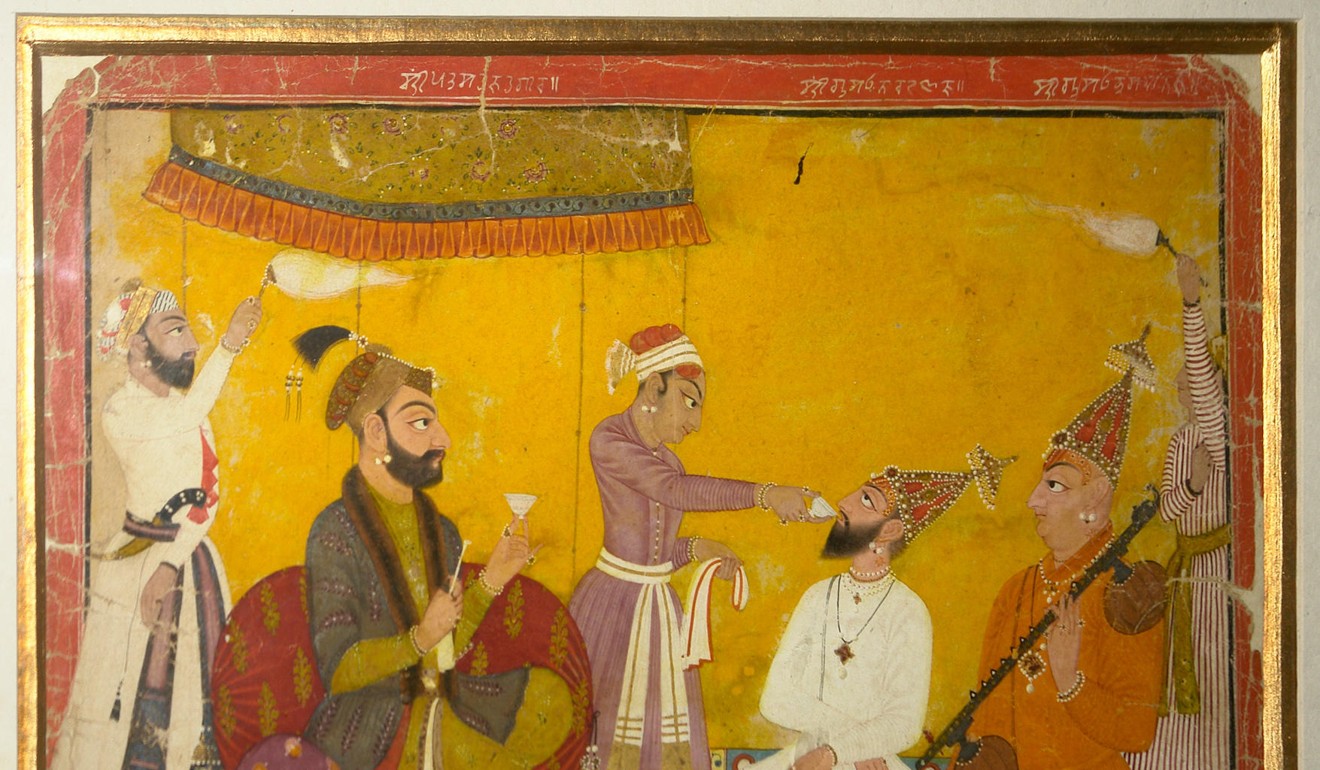

And although peasants slurped down their khichdi, even the meat-loving, excess-driven, opulence-obsessed mughals (1526-1857) condescended to eat this one-pot dish, though only after elevating it with musk, rose water, nutmeg, pistachios and raisins, and silver leaf as a garnish.

“Khichdi is the taste of mother India,” says Salma Husain, food historian and author. “It’s a simple dish that has been with us since ancient times. It is staple food for both rich and poor which has hardly changed over the years. It’s the dish for every season, every region and every community.”

In Andhra Pradesh, in the southeast, people add minced lamb to their khichdi. In coastal regions, it’s fish. In Maharashtra, Mumbai’s state, sago seeds replace rice. In Tamil Nadu, south of Andhra Pradesh, khichdi is made spicy with peppercorns. In Kerala, in the deep south, it is made sweet with cardamom and dried fruits.

Mughal Emperor Jahangir (who reigned 1605-1627) had khichdi made with millet when his digestion was sluggish; others have it with eggs or prawns cooked in coconut milk.

Khichdi has tended to be a dish eaten at home, but recently top chef Vineet Bhatia has served a black olive khichdi embellished with rosemary chicken tikka and chilli pipette at his eponymous London restaurant, and Manish Mehrotra, chef at New Delhi restaurant Indian Accent, has put khichdi on the menu of his new restaurant in New York.

How chicken Manchurian found its place in Indian cuisine

And Calcutta now has a restaurant that serves nothing but khichdi.

“My friends thought I was mad,” says Saket Kandoi, owner of Khichdi Khichdi. “Who in their right mind would want to pay for something you can make at home? But it’s so simple, so good, that I think it [...] definitely qualifies to be the national dish.”

Kandoi says he wanted to set up a soup kitchen in Calcutta for street children but realised that soup doesn’t really work in India. It’s not a staple. He decided instead to serve something all the children would be familiar with and like, khichdi, which can also be wholesome and nutritious.

“I soon realised that to be financially viable, my khichdi kitchen had to make money. So I started the restaurant. This way, the price of one order of khichdi is enough for me to give one portion to one child,” Kandoi says.

His restaurant offerings, served in clay pots that are in keeping with the dish’s rustic origins, include one made with sprouts and another with kidney beans and chickpeas, for a protein overload. His favourite, he says, is the salad khichdi, made with 24 ingredients. A version that is popular with customers is baked khichdi, which, I confess, I had never heard of.

Kandoi happens to be friends with renowned chef Gaggan Anand, owner of the eponymous restaurant in Bangkok, Thailand. On a visit to Calcutta, Anand spent some time in Khichdi Khichdi.

“He thought it was a great idea,” Kandoi says. “For me, that was the ultimate seal of approval.”