ST. LOUIS • Stephen Hempstead, a wealthy newcomer in 1811, regarded this wilderness town as “the most immoral place I ever knew.”

His was a common first impression among the pious. Roman Catholic Bishop Benedict Flaget of Bardstown, Ky., was distressed by the lax practices of his fellow communicants during a visit in 1814. Six years later, Methodist preacher Jesse Walker pledged to battle this “fountain-head of devilism.”

Their zeal bore fruit. By the 1820s, the map of the town’s religious formation was taking shape.

St. Louis was Catholic by law during its four decades as a French and Spanish colony. Mission priests served here periodically, but the first log church wasn’t built until 1770, six years after the town was founded. The parish got its first full-time pastor, the Rev. Bernard de Limpach, in 1776.

The original town plan included the “church lot,” the only city parcel never to change hands. The fourth church on that site is today’s Old Cathedral, near the Gateway Arch.

After the United States took over in 1804, the migration of Americans accelerated. Overwhelmingly, they were Protestants. Because most of them moved here to farm, not work in a city dominated by “popery,” a few Protestant congregations were formed in outlying areas before things got organized in St. Louis.

Hempstead, a veteran of the American Revolution and a sturdy Presbyterian, became the driving force in establishing the town’s first Protestant congregation. He helped recruit the Rev. Salmon Giddings, of the Connecticut Home Missionary Society, who founded First Presbyterian Church in 1817. It met in a house at Market and Fourth streets.

The Rev. John Mason Peck helped establish and preached at First Baptist Church in 1818. Its building, at the southwest corner of Third and Market streets, was the first Protestant church building in town.

Episcopalians first gathered in 1819 in a building at Walnut and Second streets. First Methodist Church was founded in 1821 and soon built a log church near Fourth and Walnut.

The Catholics, led by bishops Louis DuBourg and then Joseph Rosati, created St. Louis Academy, forerunner of St. Louis University, in 1818; invited the Daughters of Charity to open the city’s first hospital, at Fourth and Spruce, in 1828; and dedicated their cathedral in 1834.

Harvard-educated Rev. William Greenleaf Eliot established the Unitarian Church of the Messiah in 1834 and later co-founded Washington University. United Hebrew Congregation, the town’s first Jewish assembly, began meeting in 1837 over a grocery at Second and Spruce streets.

German immigrants created their first congregation, the Evangelical Church of the Holy Ghost, at Seventh and Clark streets, in 1834.

By 1860, the city had 66 houses of worship, 32 religious schools, 13 church-sponsored orphanages and eight convents. The skyline was thick with steeples.

First black minister founds church, buys freedom for slaves

John Berry Meachum was born a slave in Virginia, where he learned carpentry. Allowed to work for pay, Meachum bought freedom for himself and his father.

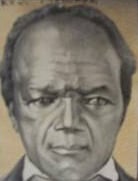

The Rev. John Berry Meachum, a former slave in Virginia who was founding pastor in 1827 of First African Baptist Church in St. Louis. A skilled carpenter, he bought his own freedom, that of his family and of about 20 other slaves. He also established a school for blacks on a steamboat in the Mississippi River after the Missouri Legislature outlawed educating blacks, slave or free, in 1847.

In 1815 he arrived in St. Louis married to a slave woman from Kentucky. He bought her freedom, too, and established himself as a skilled barrel-maker.

First Baptist Church held Sunday school for blacks, and Meachum was a regular. In 1827, he became founding pastor of First African Baptist Church, the town's first black congregation. It built a church on a site just east of today's Busch Stadium.

First African Baptist soon had more than 200 members, most of them slaves whose masters allowed them to attend. It held classes in reading and arithmetic.

But in 1847, Missouri banned educating blacks. Undeterred, Meachum obtained a steamboat and continued instruction in the Mississippi River, safe from Missouri laws. Students rowed to class.

He also bought freedom for 20 more slaves. In 1854, Meachum was fatally stricken at age 64 while preaching a sermon. He is buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery.

A French nun teaches and prays in the wilderness

Rose Philippine Duchesne grew up in a wealthy family and entered the convent in her native Grenoble, France, in 1787. She yearned to be a missionary to faraway Native Americans.

A depiction of Mother Rose Philippine Duchesne, of the Sacred Heart order of nuns, late in life. Mother Duchesne, a native of France, moved to America to serve Indians but didn't get that wish until she was 72. Meanwhile, she helped to found free schools for girls in the St. Louis area. She died in 1852 at age 83 in St. Charles.

She reached St. Louis in 1818 as a 48-year-old member of the Society of the Sacred Heart. Even then, she didn't get her wish.

The Rev. Louis DuBourg, bishop of the Lousiana territory, recruited Duchesne to America to serve Indians. But when she reached St. Louis, he sent her to open a free school for girls in the village of St. Charles. It moved one year later to Florissant, where she finally opened a school for Indian girls in 1825.

But by then, the last tribes were being forced from Missouri, and she couldn't attract students.

At age 72, Mother Duchesne finally served at a mission for the Potowatami tribe in present-day eastern Kansas, where the Indians called her "woman who prays always."

After one year, poor health forced her back to St. Charles, where she died at 83 in 1852. She was canonized a saint in 1988. Her remains are interred on the grounds at the Sacred Heart Academy grade school in St. Charles.

"How little I have accomplished," she wrote in 1850.

How wrong she was.