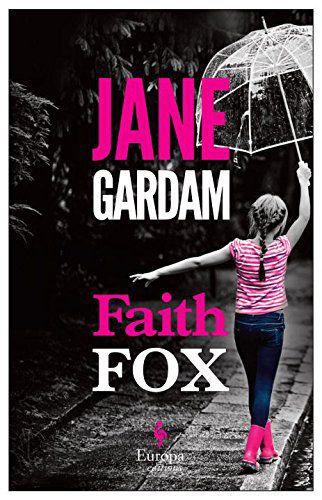

With a round-eyed stare and a gurgle, Faith Fox drives the plot, puts the characters through their paces, and even engineers a Christmas miracle in “Faith Fox,” a cleverly wrought British import.

This tiny child, just a few months old, is a potent symbol that exercises a disproportionate influence on the world around her.

And what a world it is, for baby Faith arrives on Earth in the waning days of the British Empire. Like much of author Jane Gardam’s work, “Faith Fox” is rich in elements of farce: doddering military men saddled with nicknames like Goofo and Puffy drifting in and out of reality; privileged matrons dashing from gardening to golf; and a series of hilarious missed connections. (Cellphones have not yet sprung up everywhere to ruin the humor of miscommunication in this book, a Europa reissue of a 1996 publication.)

Giving birth to the baby was the final act of Holly Fox, the doted-on only child of an upper-crust mother, Thomasina, who promptly disappears when she learns of Holly’s death.

Who will care for the child? Her father, an overstressed physician, has no time and apparently little interest. His parents, Dolly and the irrepressible Toots, deemed too old to handle a child, live at London’s opposite cultural pole, the north of England. Even more remote is his brother, Jack, a dreamer and religious aesthete who is as charismatic and handsome as he is incompetent to care for himself. He runs a huge, drafty church/charity, The Priors, and it is there that Faith’s father chooses to deposit her. At the time, a crew of Tibetans is in residence, one of whom quickly takes charge of the baby.

Faith with a lowercase “f” takes many forms in the novel, from the Tibetans’ ubiquitous and proliferating images of an eye to the collection of rather awkward silent prayers we are allowed to eavesdrop on at Christmas services at The Priors.

One delectable aspect of Gardam’s storytelling is the way she makes a point, sharply, with just a handful of words: Of an elderly socialite seized by convenient waves of dementia, she writes: “She was wearing Wellingtons. Her fur coat was over a chair; her skin luminous with money and French creams.”

Of the denizens of the airport in Cairo in a sandstorm: “No Egyptians were to be seen except for those bundles of rags blurred into mummified shapes all over the lounges, the duty-free, perhaps even the runways, sleeping till the sand had settled and drifted away.”

And when the invalid Toots wept, tears “wandered down his face to his neck” toward his pajamas of raspberry-striped “winceyette” as his wife carried away the “brimming plastic urine conch.” Gardam may speak British, but we can picture the scene perfectly.

That Gardam is a virtuoso of structure creeps up on you until you begin to glimpse the outlines of the multiple subplots converging with the satisfying click that reminds you that you’re in the hands of a master.

Helen T. Verongos is an editor at The New York Times.