In ancient Chinese dynasties it was standard practice for new rulers to destroy all symbols of their predecessors to ensure their legacies did not endure.

A recent Taiwanese legislative motion to remove all tributes to Chiang Kai-shek, the former Kuomintang leader and dictator, is not merely a continuation of this practice – it is a significant advancement in the philosophy of rule.

The transitional justice bill, passed by the island’s legislature on December 5, requires the removal of all symbols related to the former strongman leader, as well as the renaming of streets and schools named in his honour. It also calls for a full investigation into Chiang’s rule and the political purges of his opponents between 1947 and his death in 1975 – a period known as the “White Terror”, when at least 140,000 people were imprisoned or executed.

Farewell comrade: why China and Vietnam are drifting apart

Some observers see the move as politically motivated, saying it might be part of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party’s effort to undermine the Kuomintang (KMT), which is now the main opposition party, by erasing the political legacy of its former leader. The Democratic Progressive Party, or DPP, is staunchly pro-independence while the KMT favours stronger ties with the mainland.

Beijing might see the moves as another effort by the DPP to remove any historical links between the self-ruled island and mainland China. Beijing believes the ultimate motivation of this “anti-Chiang” movement is to push for the island’s eventual independence. Indeed, the DPP has also long condemned Chiang for imposing an “alien” government on the island, referring to the KMT which was formed on the mainland.

Still, from Taiwan’s perspective, Chiang’s legacy has been highly controversial. Succeeding Sun Yat-sen as the KMT leader, Chiang helped overthrow China’s last imperial dynasty and establish the Republic of China. He has also long been heralded as a national hero for leading China’s war against Japanese aggression during the second world war and fighting the communists. Chiang was also praised for land reform in the 1950s that liberated Taiwanese tenant farmers. Some say Taiwan would not be what it is today had he not brought his tattered KMT to the island and paved the way to modernisation. Under his stewardship from 1950s to 1970s, the island joined South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong as one of the Four Asian Dragons economies.

Has China’s development run up against the ‘Great Firewall’?

But the deep resentment among native Taiwanese towards the former leader has also been widespread since the island embraced democracy in the late 1980s. Today, many view Chiang as a despot who repressed Taiwan’s natives and carried out purges against dissent. Historians say he is responsible for the massacre on February 28, 1947, when an estimated 28,000 people were killed in an anti-government uprising. They estimate as many as 30,000 were killed under a campaign to suppress political dissent between 1947 and 1987, which included 38 years of martial law. Official records show that up to 8,000 were executed while about 140,000 were tried in military courts.

The legislation is not to compare Chiang’s achievements with his wrongdoings, but to realise justice for victims and their families. It will also help promote reconciliation between the two main groups – immigrants from the mainland and natives of Taiwan. The two groups have long been differentiated as the privileged and the underdog under Chiang’s rein.

As Taiwan seeks a fresh start, it needs to wash away the bloodstains left by authoritarian rule. In a modern society, authoritarian rule cannot be legitimate as it infringes rights while violating freedom and democracy. While history should give Chiang a fair, objective and balanced assessment, Taiwan does not need a reminder of his bloody legacy. ■

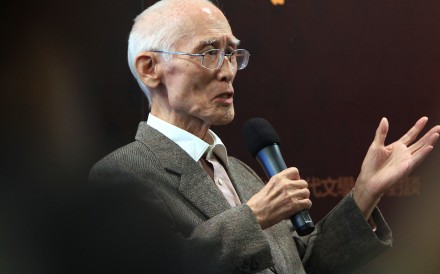

Cary Huang, a senior writer with the South China Morning Post, has been a China affairs columnist since the 1990s