Even as vengeance was like an open wound and bestiality and bloodletting carried on at the time of independence which resulted in partition and one of the largest cross border migrations that history has ever seen, these were existent circumstances where emotion drove everything. In parallel, a war was being fought in Kashmir as the new Government of India tried its utmost to save the recently acceded state. As it is said, the currency of war is information, otherwise you are off the grid. So just as India's newly birthed administration tried to work out the mechanics of the mass migration in what had become a schizoid society, it was also fighting a war and in the hotbed crucible of combat, a whisper can alter the dynamics very quickly. Treading on thin ice, PM Nehru's core team had other issues to grapple with. Issues which would snowball into something bitter and contentious very soon, given the frenetic rapidity of unfolding events. Not only had India won freedom, it was battling myriad problems; teething troubles. The PM's Secretariat was consumed with impending crises on evacuee property, water canal disputes among other gigantic issues. Top secret and confidential notes assessing these problems and their onset were prepared for the PM's eyes, so that he was up to speed with them. Imagine his administrative grasp that he had to deal with a wide catalogue of issues of utmost import.

In this treatise, I will highlight some of these confrontational issues which were likely to exacerbate going forward. Key personnel in the PM's Secretariat had them covered, building the narrative on evacuee property and water canal disputes with the use of several of the aforementioned documents and aide memoires:

EVACUEE PROPERTY.

How The Problem Arose.

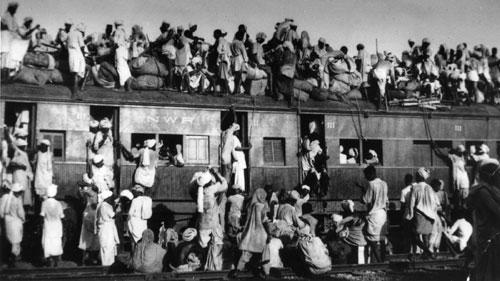

The violent communal disturbances that accompanied the Partition of India affected about 300,000 square miles in Pakistan and 87,000 square miles in India. Over five million people were uprooted from their homes in West Pakistan and forced to seek refuge in India. Similarly, five million Muslims left India for Pakistan. In addition, India had to receive nearly four million people from East Pakistan. This mass migration had the effect of almost completely denuding West Pakistan of its Hindu and Sikh minorities, while 36 million Muslims continued to live in India in peace and security.

Extent of the Problem.

The migrating refugees belonged to different strata of society. Whereas the non-Muslims coming to India were mostly landowners, entrepreneurs in industry and business, or professional men like lawyers, doctors and teachers, the outgoing Muslims belonged mainly to the poorer classes – cultivators, artisans and labourers or petty shop-keepers. The property left behind in Pakistan by non-Muslims was considerable.

According to one estimate, the value of property left behind by non-Muslims in West Pakistan was about Rs.40,000 million – six to ten times the value of property left behind by Muslims in India. In West Punjab (Pakistan) alone, Hindus and Sikhs left behind over eight million acres of land, largely rich, canal irrigated land. As against this, Muslims in East Punjab (India) and some neighbouring areas left four million acres, mostly unirrigated.

Hindus and Sikhs also left behind factories, plant and machinery and stocks of raw materials worth millions of rupees in West Punjab and other areas of West Pakistan, including Sind.

Custodians of Evacuee Property.

The magnitude of the problem was realised as early as August 29, 1947, when it was discussed at a special meeting of the Joint Defence Council at Lahore (West Pakistan) under the chairmanship of Lord Mountbatten. The prime ministers of India and Pakistan attended the meeting. It was agreed that “each Government should appoint a Custodian of Refugee Property. Close liaison between these custodians will be arranged. Representatives of India and Pakistan repeat that illegal seizure of property will not be recognized.”

On September 3, 1947, the prime ministers of India and Pakistan issued a joint statement which said : “Illegal seizure of property will not be recognized and both Governments will take steps to look after the property of refugees and restore it to its rightful owners.” The principle of restoration of property to the original owners was thus accepted by the two governments.

On September 9, 1947, the West Punjab government (Pakistan) issued an ordinance “to provide for the preservation of evacuees’ property.” A Custodian of Evacuee Property was also appointed. On September 14, 1947, the East Punjab Government (India) issued a similar ordinance. This was extended to the Province of Delhi.

To protect the property rights of Muslims who had left other parts of India to take advantage of new opportunities of employment offered by the creation of Pakistan, similar ordinances were also passed in U.P., Madhya Pradesh and certain states.

Properties Seized.

Simultaneously with the issue of the Evacuee Property Ordinance, the West Punjab Government (Pakistan) issued another ordinance to provide for “economic rehabilitation” in West Punjab. Under this ordinance, the Rehabilitation Commissioner of the Province could take over any abandoned land or business and grant temporary leases of agricultural holdings to refugees. The expression “abandoned” meant any business or undertaking which had “ceased wholly or partially to operate owing to the flight of its owners or any of the employees (including workmen) from the province in consequence of the late disturbances.” Thus even if a business failed to operate partially owing to the absence of workmen – and there was no business in West Punjab which did not so fail to operate – it would be taken over by the Rehabilitation Commissioner for the use of displaced persons. This ordinance was in letter and spirit a violation of the statements of August 29, and September 3, 1947.

On December 1, 1947, the West Punjab Government issued another Ordinance by which the Custodian could refuse to return an evacuee’s property and even prevent an evacuee from transferring his property if he felt that such a course militated against the rehabilitation of displaced persons. This amounted, in India’s view, to illegal seizure of property by a government which had declared that “illegal seizure will not be recognized”.

Inter-Dominion Conference in Delhi.

An Inter-Dominion Conference at Secretariat level held in New Delhi from December 18-20, 1947, discussed these ordinances. The conference decided that each Dominion should furnish its own scheme for the treatment of evacuee property, both movable and immovable, to a joint committee of officials by January 5, 1948.

Owing to a delay in the time table of the conference as well as Pakistan’s unwillingness to revise their Ordinance, the East Punjab Government, on January 2, 1948, amended their evacuee property law to bring it into line with the practice in Pakistan. On January 26, 1948 the law in Delhi was likewise amended, but the law in other provinces remained lenient as before.

The joint official committee met from March 22-25, 1948 at Lahore and adopted an agreed scheme under which property was divided into three categories – agricultural, urban immovable and movable property. The following measures were recommended :

Agricultural property : there should be an exchange of agricultural property at Government level, the difference in value being paid by the debtor Dominion to the creditor Dominion in the form of bearer bonds. Till the exchange was complete, the rents on evacuee agricultural property should be collected by the two Governments on behalf of the owners and the difference paid by one Dominion to the other.

Urban immovable property; including commercial and industrial undertakings, factories and workshops : the Provincial Governments should be given the right to acquire or requisition such property on payment of fair compensation to be determined by a Joint Government Agency. In other cases, the owners should be free to dispose of their property by sale or exchange. A Joint Assessment Board should be established to ensure that owners of urban property received the income from their property till sales and exchanges could be arranged.

Movable Property : Evacuees should have the right to manage or dispose of their property by themselves or through their agents. In the case of movables requisitioned by government, full compensation should be paid.

While the Government of India agreed to accept the scheme immediately, the Pakistan Government was reluctant to come to any decision, although senior Pakistan officials together with Indian officials were responsible for framing the scheme.

Inter-Dominion Conference at Lahore.

On July 22, 1948, an Inter Dominion conference at Ministerial level met in Lahore to consider the scheme submitted by the Joint Official Committee. The main question to be decided was that of agricultural property. The Official Committee had recommended an exchange of agricultural property at government level. The Pakistan representatives, however, said they did not have enough data in regard to agricultural land to come to a definite decision. It was, therefore, decided that special Revenue Officers should be appointed by the two Dominions and revenue records copied immediately.

No agreement was reached on urban immovable property. As regards movable property, the scheme suggested by the Joint Committee was accepted.

Pakistan’s attitude.

Pakistan, however, did not implement the agreements. They did not complete the exchange of agricultural records. While India supplied the records of East Punjab and Delhi and the states of Patiala, Nabha, Jind, Kapurthala and Faridkot, Pakistan gave India the records of only West Punjab and did not supply the records of Sind, N.W.F.P. and Baluchistan and the states of Bahawalpur and Khairpur as it had agreed to. The Joint Urban Assessment Board was not allowed to be set up. Instead of giving facilities for movable property to be disposed of, the Pakistan Government started taking over the property. No compensation was paid.

In October, 1948, two new Central Ordinances were promulgated by the Pakistan Government, one covering evacuee property and the other dealing with the “restoration of the economic life of Pakistan.” According to these ordinances, if one of the partners of a business left for India, the whole business become evacuee property. Powers were also assumed in the whole of Pakistan to utilise the rental income of evacuee property for the benefit of refugees in Pakistan.

Permit System.

Meanwhile, on July 19, 1948, the Government of India introduced a Permit System between India and West Pakistan, by which no person could come to India from West Pakistan without a permit from the High Commissioner for India at Karachi or the Deputy High Commissioner at Lahore. According to the Government of India, the permit system was necessitated by the return of a large number of Muslims who had migrated to Pakistan. While the government of India welcomed this sign of returning confidence among the Muslims, they felt they owed a duty also to the non-Muslim displaced persons. They, therefore, suggested to the Pakistan Government a planned return of displaced persons to their original homes.

Pakistan gave no reply, but raised the question at the Lahore Conference of July 22, 1948. India offered to withdraw the Permit System if the two Dominions could evolve “some system of regulating a two-way, as opposed to one-way, traffic.” Instead of accepting this offer, Pakistan imposed a permit system of its own.

Karachi Agreement.

The next important stage in the negotiations was the Inter-Dominion Conference held at Karachi, from January 11-13, 1949. The Conference reached two important decisions. First, the rents collected from displaced persons to whom land had already been allotted should be transferred to their owners in the other Dominion. Second, displaced persons should be given facilities to arrange, on an individual basis, sale or exchange of their urban immovable properties. Until sale or exchange could be arranged, rents should be collected and forwarded to the evacuee owners.

How it was implemented.

Soon after the Karachi Conference, the Pakistan Government issued a new ordinance which required persons visiting Pakistan for sale or exchange of their properties to obtain an income-tax clearance certificate if they stayed in Pakistan more than 15 days. This was a blow to all those who had hoped to go to Pakistan to liquidate their property. Visits to Pakistan became almost impossible, as overstaying the period of 15 days would have meant imprisonment.

The Pakistan authorities also refused to collect anything more than land revenue by way of rent of non-Muslim agricultural lands allotted to the Muslim Refugees. When land was first allotted to displaced persons by the Pakistan Government, they fixed the rent at six times the land revenue. But when it came to implementation of the Karachi Agreement, the Pakistan Government said it would be “impracticable to recover anything beyond revenue dues from refugee allottees.”

In March, 1950, Pakistan reduced the rent of urban immovable evacuee property by 80 per cent. Further reductions were allowed in lieu of management charges, prompt payment, etc, regardless of the fact that many of these properties and houses were occupied either by government or government servants and well-to-do people.

The underlying object of these measures seems to have been to depreciate the value of non-Muslim evacuee property in Pakistan. By doing so, Pakistan probably thought she could compel India to accept the comparatively small evacuee property left by Muslims in India in full settlement of evacuee property left by non-Muslims in Pakistan.

Evacuee Property Law.

Though the Pakistan Government had continued to tighten up its evacuee property law, the law in India had remained lenient. Thus, while millions of non-Muslims displaced persons in India were not getting any income from their properties in Pakistan, Muslim owners of evacuee property, including the Pakistan Prime Minister, were freely receiving remittances from India. Up to about the middle of June, 1949, Mr Liaquat Ali Khan had received an income of Rs 85,000 from his properties in U.P. alone. Further, while the property of thousands of Muslims who had gone to Pakistan and subsequently returned to India was restored, the property of non-Muslim nationals of Pakistan was declared as abandoned property, and taken over by the Custodian, although they were still in Pakistan, some of them holding responsible posts under the Pakistan Government and the Karachi Corporation.

This state of affairs drew considerable criticism from displaced persons in India, who wanted the Indian law to be in line with the Pakistan law. In the circumstances, the Government of India decided to generally tighten up the evacuee property law and make it as uniform as possible. On June 19, 1949, therefore, the Government of India issued an ordinance for the administration of evacuee property in the Chief Commissioner’s provinces. As the Centre had then no powers to legislate for provinces and states, the latter subsequently issued similar ordinances. These laws, however, were not promulgated in the eastern parts of the country, including West Bengal, Assam, Cooch Behar, Tripura and Manipur, for which there was a separate agreement with Pakistan.

The June ordinance was replaced by an all-India Ordinance on October 18, 1949, after the Government of India had acquired powers from the Constituent Assembly to enact a law for the whole country. This ordinance also did not apply to the eastern parts of the country.

Another Inter-Dominion Conference.

At the Inter-Dominion Conference which met in Karachi on June 25 and 26, 1949, the leaders of the Pakistan delegation raised the point that the enactment of a new uniform evacuee property law in India was a breach of the Karachi Agreement of January, 1949, because the Indian Ordinance had extended the evacuee property law to areas other than “agreed areas” mentioned in the Karachi Agreement. The India delegates pointed out that the term “agreed areas” meant the areas to which the scheme of the Joint Official Committee of March, 1948 applied and had nothing whatsoever to do with the application of the evacuee property law. Both at the time of the Official Committee’s report and the Karachi Agreement, there were areas in India outside the “agreed areas” where evacuee property law existed. Similarly there were areas within the “agreed areas” where evacuee property law did not exist.

The Indian delegates also pointed out that the evacuee property law in India was much milder than the law in Pakistan. Under the Indian law, they said, a person became an evacuee only if he left India or was a resident of Pakistan or acquired any interest in evacuee or abandoned property in Pakistan. Since only those persons who claimed to be refugees from India were allowed use of evacuee or abandoned property in Pakistan, the treatment of such persons in India as evacuees, they pointed out, could not be regarded as unfair. Under the Pakistan law, on the other hand, any person could be declared an evacuee even if he absented himself from Pakistan temporarily. Further, even if a business or firm had closed down partially for no fault of the owners but because of disturbances in Pakistan, the owner was declared an evacuee even when he was living in Pakistan.

A meeting of the leaders of the two delegations took place later, when it was disclosed that the Pakistan Government were not agreeable to an exchange of urban evacuee immovable property at government level. They were also not willing to give a final answer in regard to agricultural property. The conference, therefore, broke down.

New Pakistan Ordinance.

On July 26, 1949, the Pakistan Government issued an Ordinance forbidding all transactions on evacuee property or the property of intending evacuees, thus virtually repudiating the only operative clause of the Karachi Agreement.

In a letter dated August 22, 1949, to the Pakistan Government, the Government of India protested against this violation of the Karachi Agreement and maintained that a satisfactory solution of the evacuee property problem could only be reached on a Government to Government basis. Both governments, it was suggested, should set up a joint machinery to make a just and fair valuation of evacuee property in either Dominion and the net liability resulting from such valuation should be liquidated by agreed arrangements.

The Pakistan Government, unwilling to take upon this liability, stated in their reply, dated September 7, 1949: “The Government of Pakistan have repeatedly stressed their inability to agree to a settlement of evacuee property claims on a Governmental basis.”

Agreement on Movable Property.

On June 28, 1950, an Indo-Pakistan Agreement was reached on the question of movable property. Under the agreement, displaced persons were allowed to remove or sell their movable property without permit, except in the case of certain specified categories of goods. The question of movable property, however, touched only the fringe of the problem of evacuee property.

Present Position.

At his monthly Press Conference on September 30, 1950, Prime Minister Nehru stated that India had proposed that the question of evacuee property should be referred to a tribunal consisting of two Judges each of the highest judicial standing from India and Pakistan. India, he said, was prepared to abide by the decision of this tribunal.

In subsequent correspondence between the two Governments, Pakistan expressed the fear that the tribunal might not come to a decision because the Judges might be evenly divided. India, however, felt that high Judicial officers would consider any matter placed before them dispassionately and would usually agree. In the event of their not agreeing, India suggested it should be for the two governments then to either come to a settlement directly or find some other way of settling the dispute or refer the remaining points in the dispute to a third party.

Its final culmination came in 1950 with the creation of an Act:

(1) This Act may be called the Administration of Evacuee Property Act, 1950.

(2) It extends to the whole of India except the States of Assam, West Bengal, Tripura, Manipur and Jammu and Kashmir.

2.Definitions

.- In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires, --

(a) "allotment" means the grant by a person duly authorised in this behalf of a right of use or occupation of any immovable evacuee property to any other person, but does not include a grant by way of lease;

(b) "Custodian-General" means the Custodian-General of Evacuee Property in India appointed by the Central Government under section 5;

(c) "Custodian" means the Custodian for the State, and includes any Additional, Deputy or Assistant Custodian of evacuee property appointed in that State ;

(d) "evacuee" means any person,--(i) who, on account of the setting up of the Dominions of India and Pakistan or on account of civil disturbances or the fear of such disturbances, leaves or has, on or after the 1st day of March, 1947, left, any place in a State for any place outside the territories now forming part of India, or

(ii) who is resident in any place now forming part of Pakistan and who for that reason is unable to occupy, supervise or manage in person his property in any part of the territories to which this Act extends, or whose property in any part of the said territories has ceased to be occupied, supervised or managed by any person or is being occupied, supervised or managed by an unauthorised person, or

(iii) who has, after the 14th day of August, 1947, obtained, otherwise than by way of purchase or exchange, any right to, interest in or benefit from any property which is treated as evacuee or abandoned property under any law for the time being in force in Pakistan;

Explanation I .-- For the purposes of sub-clause (iii), the acquisition of any right to, interest in or benefit from any such property as is referred to in that sub-clause by a firm, private limited company or trust of which any person or any member of the family of such person wholly dependent on him for the ordinary necessaries of life is a partner, member or beneficiary, as the case may be, shall be deemed to be an acquisition by that person within the meaning of that sub-clause.

(e) "intending evacuee" means any person who, after the 14th day of August, 1947 —

(i) has transferred to Pakistan his assets or any part thereof situated in any part of the territories to which this Act extends:

Provided that the transfer to Pakistan of any reasonable sum of money in accordance with the rules made in this behalf by the Central Government, for the purpose of financing any transaction in the ordinary course of his trade or for the maintenance of any member of the family of such person shall not be deemed to be a transfer of assets within the meaning of this sub-clause, or

(ii) has acquired, if the acquisition has been made in person by way of purchase or exchange, or if the acquisition has been made by or through a member of his family, in any manner whatsoever, any right to, interest in, or benefit from any property, which is treated as evacuee or abandoned property under any law for the time being in force in Pakistan.

Similarly, now let me turn my focus on canal disputes:

CANAL WATER DISPUTE.

Punjab’s River System

The Indus system in the Punjab consists of five main rivers, which get an annual inflow from the Himalayas of 168 million acre feet of water. About two-thirds of it is carried by the river Indus and its most western tributary, the Jhelum. These two rivers have their upper reaches in Tibet and India, but they enter Pakistan before they flow into the plains, and therefore, before large extraction of water for irrigation is possible. Another tributary, the Chenab, lies in its head reach in the Indian Punjab and Kashmir, but enters Pakistan soon after it emerges from the Himalayas. The rivers Ravi and Sutlej pass through both India and Pakistan, while the river Beas lies wholly in India.

Irrigation Policy in United Punjab.

When plans were made to utilise this wealth of water, the Government of undivided Punjab took up first the comparatively easier and more remunerative schemes of irrigation. Accordingly, the Crown Waste lands in West Punjab (now in Pakistan) were exploited, bringing large financial returns to government by their sales. The proprietory areas in East Punjab (now in India) were neglected for a long time. After 1872, no major irrigation work was taken up in East Punjab, and it was only just before partition that work on the Bhakra Dam Project, to store monsoon supplies on the Sutlej or irrigation in East Punjab, was taken up. The result was that the western part (now in Pakistan) got the lion’s share of the water at the expense of the eastern (Indian) part.

Effect of Partition.

The Partition of India was drawn up regardless of physical, economic and other natural considerations. Accordingly, on August 15, 1947, by virtue of the Partition Act and orders, all lands including rivers and works, come to vest in East Punjab or West Punjab according to the territorial jurisdiction of the new Province.

Out of the 16 canal systems in undivided Punjab, 12 fell in Pakistan and three in India, with the Upper Doab canal divided between the two. Pakistan got 18 million acres of irrigated land as against five million in India, although out of a total cultivable area of about 85 million acres dependent for irrigation solely on the Indus system, 40 million acres lie in India and 45 million acres pin Pakistan. About 20 million people in India and 22 million people in Pakistan are dependent on the rivers of the Indus Basin.

Standstill Agreement.

Soon after Partition, on December 20, 1947, the chief engineers of East and West Punjab signed a Standstill Agreement to maintain up to March 31, 1948, subject to payment, supplies from the Upper Doab Canal in India to channels of the system in Pakistan severed by Partition. A similar agreement provided for supply of water to the Dipalpur canal in Pakistan from its headworks at Ferozepore in India.

These agreements clearly indicated that if Pakistan wanted to get any waters from rivers in India, it could be only on the basis of negotiations with India or on the basis of any award which might be given by the Arbitral Tribunal which had been specially set up to adjudicate on claims of one Dominion against the other. Pakistan had still six weeks to prefer further claims before the Arbitral Tribunal, but did not.

Before the expiry of the Standstill Agreement, East Punjab requested West Punjab to take steps to conclude a further agreement, with no result. On April 1, 1948, therefore, in the absence of any fresh agreement, supplies to canals in Pakistan from India were stopped.

On April 18, 1948, the chief engineers of the two Punjabs met with the authority of their respective governments and an

agreement was signed. This agreement recognised that East Punjab had become the owner of the Upper Doab Canal and the Ferozepore headworks as a result of the Radcliffe Award and the Instruments of Partition, and provided for the continuance of supply of water to areas in Pakistan for a limited period.

The agreement was not ratified by the Government of Pakistan, who requested that the matter be discussed at Inter-Dominion level.

India’s Claim to Water Recognised.

On May 4, 1948, as a result of an Inter-Dominion Conference held in Delhi, an agreement was reached, under which Pakistan recognised East Punjab’s need to develop irrigation in her famine areas and agreed to a progressive diminution of supply of water to canals in Pakistan. India, on her part, agreed to supply water to these canals for a reasonable period, so that Pakistan could meanwhile, tap alternative sources of supply.

In July, 1948, another Inter-Dominion Conference was held at Lahore (West Pakistan). At this Conference, the Pakistan representatives stated that a certain period would be required to develop alternative sources of water. India suggested that this could be done in seven years.

From July, 1948, nothing further was said by the Pakistan Government about this matter. India continued to supply water to Pakistan canals under the May, 1948 agreement, though there were disputes about payment of charges.

Pakistan Changes her Stand.

In June, 1949, Pakistan shifted her position and claimed, as of right and irrespective of the needs of India, that she should get in an unrestricted manner and from the same sources as before, all the supplies which she used to get before Partition. India did not agree to this for two reasons. Firstly, she held that Pakistan had no rights to waters from Indian rivers, except in so far as India might agree to provide on humanitarian grounds as a result of negotiated agreements. Secondly, India felt that if she accepted Pakistan’s claim, it would amount to signing away for all time to come her right to develop about 10 million acres of culturable waste land in the Indian part of the Punjab and the states of Bikaner and Jaisalmer, which could be done only by utilising the waters in the Indian rivers.

Pakistan also expressed the view that the three rivers flowing from East Punjab (India) to West Punjab (Pakistan) were international rivers and, therefore, India should agree to refer the matter to the International Court of Justice. India felt this was a strange proposition, because there had been numerous disputes in the past over river waters which had all been solved by negotiations, except one which was taken to the International Court of Justice mainly for the interpretation of any agreement previously negotiated between Belgium and Holland. At no stage had any independent country considered a suggestion to arbitrate with a foreign country on the use of its own natural resources.

In August, 1949, at an Inter-Dominion Conference held in Delhi, India suggested the appointment of a Joint Technical Commission to make an overall survey of the water resources of the Indus Basin, with a view to equitably dividing these supplies between the Indian and Pakistan areas of the basin. A Negotiating Committee met twice for the purpose, but could not reach any agreement because the Pakistan representatives insisted, as a preliminary to further discussion, that India should agree to the appointment of a neutral chairman of the Joint Commission. This was not acceptable to India, who held that a settlement should be by negotiations directly between the parties concerned.

Later, a separate technical examination by Indian and Pakistan experts of their own respective regions of the Indus basin took place, but Pakistan did not encourage a joint discussion between them.

Has Pakistan enough Water Resources?

Indian experts state that they can prove to Pakistan’s satisfaction that the Pakistan portion of the Indus Basin would still have sufficient water resources for its needs when the Indian supply is withdrawn. This is on the basis that supplies are available to Pakistan from the rivers Chenab, Jhelum and Indus. Geographically, it is pointed out, India cannot make any direct use of these surpluses; only Pakistan can make use of them. If Pakistan diverts them to some of her existing canals, supplies which are at present being received from India can be released for use in India. This, it is argued, is the only practical approach which will enable India to develop her famine-hit areas without causing injury to Pakistan.

Present Position.

The position at present is that Pakistan continues to receive all benefits under the Inter-Dominion Agreement of May 4, 1948. In return she continues to make payments of undisputed amounts to Punjab (India) and to deposit in “escrow” with the Reserve Bank of India the disputed amounts as determined by the Prime Minister of India.

India has suggested that the canal water dispute, like the question of evacuee property, should be referred to a tribunal consisting of two judges from India and two judges from Pakistan of the highest standing. India has stated that she would abide by the decision of this tribunal. In the event of the judges being evenly divided, India wants the two Governments either to come to a settlement directly or find some other way of settling the dispute or refer the remaining point in dispute to a third party.

These were obviously high strung and trying times, the pressure incessant and more often than not, you were dealing with a bellicose neighbour whose contempt for India had turned malignant.

(Some of the lingua franca used is set in those tumultuous times and has been retained by the writer to retain the sense of gravity, urgency and expectancy that existed at that time.)

@sandeep_bamzai