The auteur of warm-hearted comedies who was just as gentle and professorial as the films he made.

The auteur of warm-hearted comedies who was just as gentle and professorial as the films he made.

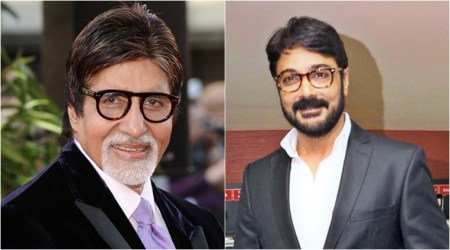

Mild-mannered, avuncular, master of simplicity, king of gentle humour, middle-of-the-road filmmaker, auteur and schoolteacher-like are some of the titles that have, over the years, been bestowed upon Hrishikesh Mukherjee, or Hrishi-da as he was fondly nicknamed within the Hindi film industry. Amitabh Bachchan, the sad-eyed Babumoshai of Anand (1971) called Hrishi-da, who died on August 27, 2006, “godfather to us.” But it was Jaya Bachchan – she stayed with the late filmmaker when she first came to Bombay and was so close to him that he was among the first people to know about her impending marriage to Bachchan – who may have hit it closer to home when she said, “Hrishi-da was like a father.” And so he was, and that’s how he behaved, with unquestioned authority of a benign but disciplinarian father, on the sets of his films. Not only to Jaya Bhaduri, but also to Amitabh Bachchan, Dharmendra, Deven Verma, Amol Palekar, and even that self-indulgent superbrat whom we know as Rajesh Khanna. Unfussily, the superstar was “Pintu Baba” to Hrishi-da.

The appeal of a Hrishi-da film cuts across people, ages and generations. Perhaps, that’s what may have led author Jai Arjun Singh to subtitle his Hrishi-da biography, The World of Hrishikesh Mukherjee, with: “The filmmaker everyone loves.” By most accounts, the Calcutta-born Hrishi-da was both much-loved and loveable, a rare Bollywood filmmaker whose cinema is so instantly familiar and recognisable that any viewer watching a Satyakam, Anand, Bawarchi, Chupke Chupke or a Gol Maal can never confuse these for films by Ramesh Sippy or Manmohan Desai. If any confusion or comparison did occur, it was between Hrishi-da and Basu Chatterjee. For, both filmmakers had notable similarities. Their gentle comedies, about honest and honourable men (usually of means) navigating their way in a world of moral corruption and rapidly disintegrating old order, often overlapped. Sometimes, the confusion deepened because they shared the same repertory of stars. It could be Om Prakash, Asrani, David or Amol Palekar. Hrishi-da’s films were simple but never simple-minded. In Chupke Chupke and Gol Maal, two of his best known comedies, there is lightness of touch but also enough sophistication of language or “bhasha” and plenty of amusing insights into the gentry, the ideas of social class and middle-class morality.

Much before he became a filmmaker, you won’t be surprised to know that Mukherjee actually worked as a teacher briefly. He learnt everything that there was to learn about filmmaking from Bimal Roy. And whatever he learnt he passed it on to Gulzar, Dharmendra and the Bachchans. When Mukherjee, essentially an editor, made his first film, Musafir in 1957 (with Dilip Kumar, Suchitra Sen and Kishore Kumar among others), he got Ritwik Ghatak to write the script. In doing so, the trajectories of the parallel cinema converged with mainstream possibilities. Reportedly encouraged into film direction by Dilip Kumar, Bimal Roy’s young assistant set out to make Musafir, a highly experimental and symbolic effort, about a house that witnesses a man’s essential rites of passage: birth, marriage and death. What is it with Mukherjee and his obsession with landlords and rents? Two years later, he directed Raj Kapoor in Anari, a down-on-luck artist who’s too good to be true for an unscrupulous world that only values wealth and power. As RK himself puts it in a scene with his landlady (a Bandra-type played with endearing sympathy by Lalita Pawar, possibly a forerunner to her matronly nurse in Anand), “Apni haalat toh iss ghadi ki tarah hai. Duniya mein koi bhi waqt ho lekin yahan har ghadi baarah baje rehte hain.”

From Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor and even Dev Anand (Asli-Naqli) and Ashok Kumar (he gave Dadamoni some of his most beloved roles, including Aashirwad and Mili), Mukherjee went on to superimpose his Bhadralok Bengali sensibility onto Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan and Rajesh Khanna. From one holy trinity (Dilip-Dev-Raj) to another (Dharam-Amitabh-Kaka), Mukherjee was a glue that bound these disparate stars in an unholy union. They all competed with one another to work with him. He gave the Bachchans their earliest break – Jaya as a schoolgirl with massive crush on Dharmendra in Guddi and Amitabh in Anand. Critics have noted that Mukherjee may have accidentally given Big B his angry young man persona in Anand where Bachchan, as Dr Bhaskar, is a grave and contemplative presence. (Elsewhere, Javed Akhtar of Salim-Javed who created the disaffected Vijay for Bachchan has cited Mili as the superstar’s most low-key angry young man performance). When Anand, played memorably by Rajesh Khanna, dies, an intense Bachchan launches into an angry outburst instead of the usual emotions of grieving and crying. That’s Dr Bhaskar’s way of dealing with Anand’s loss.

In Satyakam, which was Hrishi-da’s favourite film and nearly everyone’s favourite Hrishi-da film, too, Dharmendra is an idealist who leads by example not because he wants to appear as nobler than thou but because that’s the only path he knows that fits in with his moral rules. Later, Hrishi-da cast Dharmendra as a dramatically-inclined, prank-loving professor in Chupke Chupke who simply wants to teach the much-respected, soap-selling “genius jijaji” (Sharmila Tagore’s turn of phrase for Om Prakash) a lesson by playing a harmless practical joke on him. Most viewers equally remember Hrishi-da for Gol Maal, a side-splitting 1979 comedy featuring staples Amol Palekar, Utpal Dutt, David and Deven Verma. Once again, humour emanates from the clash of old and new-world values and role-playing. Typical of Hrishi-da films, there are meta remarks about the movie people, actors and stars. In one song, written tongue-in-cheek by Gulzar, Amol “Everyman” Palekar who was as different from Amitabh “Angry Young Man” Bachchan as Hrishi-da himself was from Manmohan “Showman” Desai, Palekar sings about replacing a “market se out” Bachchan. It was almost like Hrishi-da and Gulzar who, speaking in an interview described Mukherjee as “Masterji” and himself as “one of his better students” were LOLing long after the joke was cracked.

Jhooth Bole Kauwa Kaate, in 1998, was Hrishi-da’s last film. It wasn’t a box-office success. Comedian and director Sajid Khan, who worked in Jhooth Bole Kauwa Kaate, told a reporter in 2008, “I have never been an assistant director to anyone, but I carefully observed Hrishikesh Da’s style of filmmaking. His films had substance.” The fact that Hrishi-da’s influence and traces can be found in filmmakers as diverse as Sajid Khan and Rohit Shetty on one hand and Raju Hirani and Shoojit Sircar on the other is a testament to his enduring relevance not only among viewers, young and old alike, but also among those who make and shape cinema.

(Shaikh Ayaz is a writer and journalist based in Mumbai)