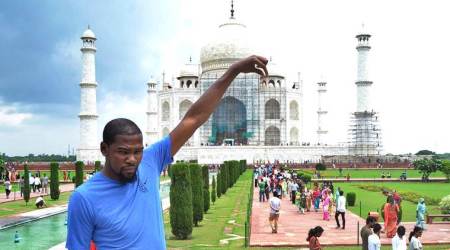

Indira Gandhi addressing a rally in 1979. Express Archive

Indira Gandhi addressing a rally in 1979. Express Archive

Title: Indira, India’s Most Powerful Prime Minister

Author: Sagarika Ghose

Publications: Juggernaut Books

Pages: 342 pages

Indira Gandhi’s was a tempestuous and turbulent life that, as the author of this lucid and eminently readable new biography concludes, mirrored that of India itself. When she became Prime Minister in January 1966, few expected her to be master of the house; but, three years later, she not only took on the syndicate of senior Congressmen who had put her in South Block, but went on to lead her party to a plebiscite-like victory in the 1971 general elections. More than any leader other than Jawaharlal Nehru, she redefined the powers of the office, the nature of the polity and India’s place in the wider world.

Ghose brings few new documentary sources to light, the Indira Gandhi papers not being open without special permission. The writer makes up for this with deft use of earlier biographies and with many interviews with survivors of the past era. The result is a whirlwind tour that combines the personal and the political, the changes in her household and inner circle with those in the Congress, the political system and in world affairs during the Indira era.

The term “era” is not be used lightly, but, by 1969, there was a veritable remaking of the political order under way. A more centralised system emerged both in the party replacing the regional satraps, even as the Congress used every trick in the book to expand its base against rising rivals of every hue in the states. The victory in 1971 on the promise of abolishing poverty was followed soon after by “her finest hour” — the liberation of Bangladesh. State Assembly polls saw a clean sweep. Crisis set in soon after. With such high hopes, disillusionment was inevitable. Here, it may well be argued the turn came not in 1974, but in 1973. The failure of the monsoon and double digit inflation spelt trouble. From here, the road downhill was clear. The Emergency was an outcome of a deep political breakdown but the response was such as to deeply damage the political institutions, most of all the Congress party itself.

The book is strongest on the sweep of events and the way it places her at the centre. The sources are secondary — even a brief look at the Haksar or PN Dhar papers would have complicated the story a little. For instance, it is clear the 1966-68 phase of devaluation and Indo-US relations was significant and there were geopolitical reasons for its collapse. But the same Johnson administration and the Rockefeller Foundation helped speed the Green Revolution in India.

Bank nationalisation helped capitalism in India to stabilise by making credit available in rural areas and small towns and by the early 1980s, there was steady liberalisation by stealth. One symbol of this was the very public dinner reception held at Ashoka Hotel by the rising textile producer, Dhirubhai Ambani. The ascendancy of the IT sector owed much to many steps in 1980-84 that bore fruit some years later. This other Indira Gandhi requires more careful study.

Where the book may have done with a rethink is in the letters from the author to the late Prime Minister. They break the flow of the narrative and somehow do not add to the appeal of the volume. Further, there are more references than were due to MO Mathai, a source discredited and far from reliable.

It is difficult for any author to do justice to such a complex figure. Where Ghose deserves credit is in being even-handed in acknowledging sterling achievements but being unsparing in criticism. The installation of Sanjay Gandhi as heir apparent by late 1976 was, indeed, a turning point in the history of the Congress. Similarly, the communal card played in her final years not only stoked fires in Punjab but prepared the grounds for deep divisions in the social fabric that persist to this day.

On both counts, however, Indira Gandhi was not alone. Most parties in India save the cadre-based formations have been taken over by kinship groups. As for inducting sectarian groups into politics, the Congress had already aligned with the Muslim League in Kerala long before. Nor did her successors show any major break in this regard. Yet, far more than her personal predilections, did the Eighties mark a major shift in state-society relations with the larger ideal of commonalities in the freedom struggle giving way to other identities?

All in all, the book is a compelling read and carefully balanced in the tradition of the classic biography by Inder Malhotra. The photos are not only well chosen, but add to the insights on Indira as an early woman politician at the helm of affairs of a large nation state. At the end, the book’s prose lingers in the mind, and the subject remains the enigma she will be even a century after her birth.