The RJD, on the other hand, calls its own ouster from the ruling coalition and the swapping of places with the BJP, the party defeated by the JD(U)-RJD pre-poll Mahagathbandhan, as the people’s betrayal.

The RJD, on the other hand, calls its own ouster from the ruling coalition and the swapping of places with the BJP, the party defeated by the JD(U)-RJD pre-poll Mahagathbandhan, as the people’s betrayal.

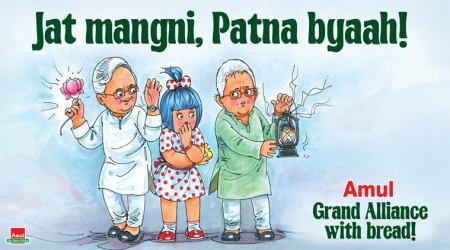

In Patna, all three parties involved in the unceremonious unmaking of a 20-month government and the hurried cobbling together of a new one invoke “the people”. Nitish Kumar, Sushil Modi and Lalu Prasad speak vehemently of the mandate of 2015 — the first two to give a patina of respectability and legitimacy to the series of hidden chess moves and secretive manoeuvres that, overnight, rearranged Bihar’s ruling arithmetic. The people didn’t vote for corruption, they say. The RJD, on the other hand, calls its own ouster from the ruling coalition and the swapping of places with the BJP, the party defeated by the JD(U)-RJD pre-poll Mahagathbandhan, as the people’s betrayal.

About an hour and a half by road from Patna, lies Raghopur, the constituency of Tejashwi Yadav, son of Lalu Prasad and deputy chief minister of the unseated Mahagathbandhan government. Raghopur is seen as a Yadav bastion, which in the past has elected both Lalu and his wife Rabri Devi. Here, the clearest articulation by the people of a mandate betrayed or hijacked is to be heard in the Muslim mohalla (which holds up one half of the M-Y combination that has shored up Lalu’s political longevity in the state).

In the conversations in Daudnagar village, you can also hear insecurity about what the new government might bring for Muslims. And the unmistakable closing of ranks behind Lalu. “Bihar voted for the Mahagathbandhan this time, not for the BJP. If people wanted to vote for it, the BJP would have won. Now, Nitish has done gaddari, dhokebaazi (deceit) with us,” says 23-year-old Mohammad Shahbaz.

“We turned to Nitish when he broke away from the BJP”, says Shahnawaz Khan, who works as a land surveyor. But “Nitish only used Lalu to win an election because he wasn’t confident of winning a third term with the BJP or on his own, and then did a ghar wapsi. He had planned this all along”, says Shahbaz. Others mockingly recite a Nitish promise made earlier: “Mitti mein mil jaayenge, BJP ke saath nahi jaayenge (I will never go with the BJP again, at any cost).”

There is talk of the incidents of lynching in the name of the cow in other states, and the anti-Romeo squads of Uttar Pradesh. “So far, this has not happened in Bihar”, says Shahnawaz Khan, “But who knows what will happen now that the BJP is so powerful at the Centre and is also in government in Patna. They are much stronger now”, he says.

*****************************

Away from the Muslim huddle in Raghopur, the indignation over the bringing down of the Lalu-Nitish government and installation of the Nitish-BJP regime is a more mixed thing. Among the Yadavs, they speak of Nitish’s perfidy, but not of a hijacked mandate. Nitish’s move is not seen as opening the door to religious polarisation. Narendra Modi is no spectre here — in fact, he has already succeeded in getting a foot inside the door.

Many Yadavs in Lalu’s bastion voted for Modi in the Lok Sabha election of 2014 — and admit to doing so too. For them, the two elections involve two separate sets of calculations; there is no contradiction, awkwardness or disloyalty in voting for Lalu in an assembly election, Modi for the Centre. Many of them also own up to voting for Nitish in the state elections — in Lalu’s name, as part of the Mahagathbandhan, but also while he was still with the BJP.

There are still assertions of undying caste loyalty to Lalu, his family, and his party, in his bastion — “we will vote Lalu, win or lose” — or “because Lalu gave us a voice, yeh sab unhi ki den hai (he has given us everything)”. Yet, in their own telling, at least some of the Yadavs of Raghopur have also been looking for another reason to vote. Nitish gave them the incentive to step out of the comforts of the caste fold — it was called “development”. After all, for all their heady gains in terms of the empowerment of backward communities, and especially the Yadavs, the Lalu years were made up of very real bijli-sadak-paani failures and absences that most affected these groups. “Development” also provided reasonable cover to those who voted for Nitish simply because they were fatigued with living in a vote bank.

For the moment at least, however, the closing of ranks, by and large, of the Yadavs behind Lalu, in the wake of the Nitish “betrayal”, may be interrupting, if not reversing, this new negotiation that has been afoot between the voter and caste loyalties in the state. Raghopur, the Yadav family stronghold, is an especially interesting site to track this change and in the past few days, its rollback.

In Terasia village, listen to Mani Bhushan Prasad Yadav: “People in my state vote more for jaatiya sameekaran (caste), not gun-avgun (accomplishments of the leader)”, he begins with the truism. But “I became a BJP supporter ever since my MLA delivered on the promise, long-dishonoured by Lalu’s family, of building a high school in my village”. The MLA in question, Satish Kumar, then in the JD(U), subsequently switched sides to the BJP. Mani Bhushan Yadav says he has been disenchanted by Lalu’s “karya shaili”. “Historically, those who work only for their own family, don’t have a future — look at Mulayam Singh Yadav, look at the Congress, or even Ram Vilas Paswan, all dying a slow death politically, in 10 years if not now”, he says.

For him, the recent Nitish-BJP manouevres have only further shown up the RJD’s inability to keep up with the times: “Look at what has happened in Bihar, Manipur, Goa. Aap prayas kyun nahi kiye (why did the RJD-Congress not make more of any effort to save the Mahagathbandhan government)?” he asks. Had Tejashwi resigned, he says, “unka maan-samman barh jaata (he would have gone up in the people’s esteem). After that, even if Nitish had walked out, he would have looked the smaller man”. Listen to Mantosh Yadav, 25 years old, also from Terasia. “We voted for Tejashwi, not in Lalu’s name, but because he was walking on Nitish’s path. Lalu may not have changed his politics over the years, but his son was different. Nitish should have dismissed Tejashwi, we would have re-elected him (Tejashwi), and everything would have been okay. Raghopur ki janata insaf kar deti”, he says.

“The guardian of the Mahagathbandhan was Nitish. But he was more interested in his own chair”, says Sudhir Kumar Yadav, 27 years old and unemployed. “If there is an election today”, he hazards a prediction, “and all three fight separately, it will be BJP in first place, RJD second and Nitish in third place”. Many Yadavs here admit to voting for the JD(U) candidate Satish Kumar in the election that Rabri Devi lost in 2010. “We wanted to give him (Nitish) a chance because of his work in his first term”, says Lal Bahadur Rai, mukhiya, in Diwantok village, who now fiercely proclaims loyalty to Lalu.

For the moment, bitterness against Nitish for ousting Lalu from government is gaining the upper hand.

For the moment, bitterness against Nitish for ousting Lalu from government is gaining the upper hand.

For the moment, bitterness against Nitish for ousting Lalu from government is gaining the upper hand. There is talk, in the group in Terasia and elsewhere in the constituency, of “Kursi Kumar”. Many say that Narendra Modi was right when, during the 2015 election campaign, he launched a personal attack, which at that time was seen to have boomeranged, on Nitish’s “gadbad (faulty) DNA”.

As for the reason ostensibly at the centre of the regime change in Patna — corruption — the Yadavs of Raghopur are wasting no time over it. The manner and machinations behind the felling of the Mahagathbandhan government have completely overtaken an issue on which there is already a deep ambivalence and cynicism. “Who is not corrupt, chor toh sab hain. But it is only Lalu who is being targeted”, says Mangru Rai. Others like Nanabir Prasad Yadav ask: “Where is the justice in punishing the son (Tejashwi) for the sins of the father?”

*****************************

The anger welling up against Nitish after the events of the last few days is sharpened by, and joined together with, the perceived backsliding over a longer period in what was seen to be his USP. There are stories in Raghopur of how the prashasan (administration) that became so “tight” in Nitish’s first two terms — in terms of enforcing law and order, revival of the government school, and building of bridges and roads — is becoming “loose” again in his third term. The reason for that, they say, is not any pressure by Lalu, but simply a slackening on the part of Nitish.

Many point to the slide in the school which serves khichdi but very little education. Akhilesh Kumar Rai, in Mile village, Bidupur block, talks of increasing “police ki manmaani (arbitrariness)” and bribe-taking. Most of all, the talk is about how prohibition is failing on the streets and in the mohallas, cocking a snook at the very authority of the state that Nitish had played such a crucial role in reinstating in his first and second terms.

Nawal Rai, who works as a painter in Delhi, says: “You can see how the Nitish administration is defied here daily. Did alcohol stop flowing in Bihar? Where is his much touted governance?” Alcohol in all its versions, is still available, they say, only more expensive. In the popular telling, Nitish’s perceived perfidy vis a vis Lalu is now being tied up with the slide in his own developmental record. Of course, in a twist typical of Bihar, the story changes, dramatically, in the Dalit and EBC clusters of Raghopur. Here, what the Yadavs and Muslims see as Nitish’s perfidy is hailed as a moment of liberation from the domination and oppression of the Yadavs and the party that speaks for them.

In the Harijan tola of Terasia, Meena Devi speaks in low and vehement tones: “What has happened is all for the good. The Yadavs monopolise everything, leave nothing for us. We gave Tejashwi our vote, got nothing in return.” Dimple Devi says “Nitish has done well to join hands with Narendra Modi. Modi ji gave us gas connections, electricity. Now we hope that, together, they will do something for us. We want homes, land of our own. We want toilets. The Yadav babus watch us when we defecate in their fields. We are always at their mercy, we have nowhere to go”.

And in the Harijan tola of Saraipur, Kavinder Das says: “It is true that Laluji gave us a voice, but that is an old story. Now, for 20 years, there is only drama in our name. Nothing changed for us when Rabri Devi became CM, or with Tejashwi as deputy CM. Modi is doing good work, notebandi has got out the black money. Nitish had to pull out the rug from under the Mahagathbandhan government suddenly in the night because the Yadavs would have run riot otherwise”.

*****************************

On balance, a straw poll, taken today in Raghopur, may well throw up the following results: The BJP, already a clear choice for the Centre, has gained a further foothold in the state. The RJD is a gainer too, of sympathy from even those who had broken caste ranks, to gravitate towards Nitish, in the state. The loser in Raghopur is Nitish. You could say that Lalu’s bastion was not his to lose. But that may not be entirely true.

And if those who make up the cast of characters in Bihar are also to be seen as carriers of larger narratives, you might go so far as to say this: For now, as caste raises its head again in Raghopur, it is development that has been cast into the shade.