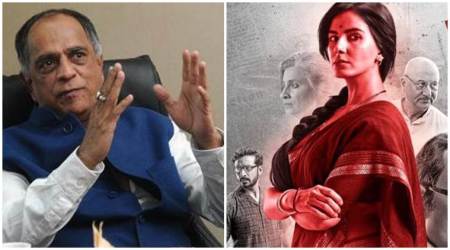

Indu Sarkar, starring Kirti Kulhari in the lead role, releases across India on July 28, 2017.

Indu Sarkar, starring Kirti Kulhari in the lead role, releases across India on July 28, 2017.

Madhur Bhandarkar’s Indu Sarkar, a tale set in the Emergency period of 1975-77, is all set for release tomorrow. The pre-release days of the film have seen a fair amount of buzz and controversy, primarily due to the objections and court petitions seeking a stay on the release, by Priya Singh Paul, who claims to be the biological daughter of late Sanjay Gandhi — a key figure of Emergency and in the film, played by Neil Nitin Mukesh. Paul claimed it was her effort to ‘protect her family’ in spite of the fact that the filmmakers have claimed that seventy per cent of the film is pure fiction. While Paul’s petition has been rejected by the Supreme Court, it served to keep Bhandarkar and Indu Sarkar in the news.

It is all too common these days for a movie to come with its dose of controversy. In case of Aligarh (2015), a Muslim outfit was unhappy with the title and unsuccessfully appealed to Pahlaj Nihalani to have its title changed. Several objections, from Peshwa’s descendants and the Chitpavan Brahmin community, surrounded the release of Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s film Bajirao Mastani (2015). Less than a month before the release of Vidya Balan starrer The Dirty Picture in 2011, the Mumbai Mirror reported that V Naga Vara Prasad, brother of late Silk Smitha — the namesake of Balan’s character — had sent a legal notice to the film’s director Milan Luthria and producer Ekta Kapoor for making the film without the family’s permission. The film, however, released as scheduled.

Somewhere many of us become more aware of and remember certain films because of the obstacles that marked them. This paradoxical nature of an individual or a group’s objections or bans on films, that they end up generating a cloud of pre-release publicity and serve to pique audience interest, makes them a fertile ground for suspicion and conspiracy theories. Is it possible, one wonders at times, that last minute controversies could be sought after by the film producers too?

The list of movies running into crosshairs with individuals, groups, governments and CBFC is very long and the actual threat posed to the film by an objecting party is quite variable by the case.

Aandhi (1975), starring Suchitra Sen and Sanjeev Kumar, was banned while Indira Gandhi was in power.

Aandhi (1975), starring Suchitra Sen and Sanjeev Kumar, was banned while Indira Gandhi was in power.

Films like Aandhi (1975), loosely based on Indira Gandhi’s life, and Kissa Kursi Ka (1975), a political spoof lampooning Sanjay Gandhi and Emergency, did not sit well with the Congress government. While Aandhi was banned during the Emergency and released after Janata Party came to power in 1978, all prints of Kissa Kursi Ka had been confiscated and burnt upon Sanjay Gandhi’s orders as Emergency was already declared by the time the film came to the CBFC for clearance.

The Shiv Sena also found many soft targets in movies over the years to flex its muscles and fan its reactionary ideology, most notably in case of Mani Ratnam’s Bombay (1995) where an inter-faith couple at its centre and Deepa Mehta’s Fire in 1998 (along with Bajrang Dal) where the lead female characters develop a homosexual love for each other. In the former case, the film had to be modified to be left alone and in the latter case, release was disrupted across various cities, which clearly had a serious impact on the film’s revenue. Among its later targets for threats of disruption have been movies like Shah Rukh Khan’s My Name is Khan (2010) over invitation extended by the latter to Pakistani cricketers to play in his IPL team.

Film star Shabana Azmi and Nandita Das in film FIRE. Express archive photo

Film star Shabana Azmi and Nandita Das in film FIRE. Express archive photo

Bajrang Dal and Maharashtra Navnirman Sena in the recent years have raised small and big objections to Aamir Khan’s PK, Shah Rukh Khan’s Dilwale (2015) and Karan Johar’s Ae Dil Hai Mushkil (2016), over ‘intolerance comments’ and ‘Pakistani actors’ respectively. According to one report, even Dangal (2016) could have been a potential target of the Sangh’s ire towards Aamir Khan, although it finally wasn’t.

Opening the controversy box of recent CBFC excesses, whose non-certification of a film is tantamount to a ban, is especially demonstrable in cases like Udta Punjab and Lipstick Under My Burkha, in the recent times is another rabbit hole.

One could say it is just very easy for Indians to take offense. Individuals usually do not have disruption powers, but muscular groups and powerful establishments do. Their reasons can be communal, religious, personal, political wariness or benefit. Usually they are effectively harmless, even backhandedly beneficial, to the movie — especially if it is backed by an influential name and industry, which ensures bargaining capacity to forestall its burial. But every once in a while when law and order fails filmmakers, bans and release disruptions have been a very real, very undesirable nuisance.