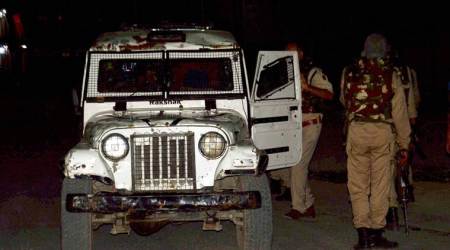

Amarnath yatra attack is the continuation of a cynical and sinister attempt by terrorists to exploit the feelings of isolation and disenchantment that inform the identity of young people in Jammu & Kashmir. (File photo)

Amarnath yatra attack is the continuation of a cynical and sinister attempt by terrorists to exploit the feelings of isolation and disenchantment that inform the identity of young people in Jammu & Kashmir. (File photo)

The Amarnath Yatra terror attack has not just shaken India, but all people of conscience and decency, especially in Pakistan. For over a decade, the targeting of religious and spiritual gatherings has become a key tool in the arsenal of terrorists. Throughout the Middle East, sectarian wounds have been gouged and deepened by wave after wave of terror groups.

Outside of Iraq and Syria, perhaps no country has seen as many religious gatherings attacked by terrorists as Pakistan. The targeted community changes, the context changes, but the objective of the terrorists is always the same: to provide those that would divide us the ammunition to pour more gasoline on an already volatile set of perceptions and relations within and between communities.

The Amarnath yatra attack is the continuation of a cynical and sinister attempt by terrorists to exploit the feelings of isolation and disenchantment that inform the identity of young people in Jammu & Kashmir. Unlike the dark days of the 1990s when the contest between militant groups and Indian security forces took place away from the spotlight of ubiquitous social media, the atrocity in Anantnag has taken place in plain view of all decent people, all over the world.

It is not a coincidence that from Syed Ali Shah Geelani, to Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, to Yasin Malik, the condemnations of the Anantnag attack have been swift, unequivocal and strong. Any terror attack as heinous as the one that took the lives of seven devotees undermines the very foundation of Kashmiri resistance to Indian rule in Srinagar. It may not hold true for mainstream India, but across the Kashmir Valley, and particularly in Pakistan, Kashmiri militants can get away with, (and even be lionised for) fighting against symbols of the Indian state.

But Hindus praying at a special time and a special place is nothing but a group of believers expressing their religious devotion. Any support for Kashmiri self-determination will collapse in the face of brutality against innocent people, especially worshippers. The Amarnath yatra attack, as several Kashmiri separatist leaders have stated, goes against the very grain of Kashmiriyat. I suspect Kashmiriyat here denotes not only the unique social ethos of the state, but also the Kashmiri argument for deeper federalism, autonomy, self-determination, call it what you will.

Pakistanis know well the feelings of rage and vengeance that emerge after terror attacks against worshippers. A December 2009 attack on a Friday congregation at Parade Lane in Rawalpindi took 40 lives, including the lives of family members of serving generals in the Pakistan Army. On May 28, 2010 a double attack on Ahmadi places of worship in Lahore ended with nearly one hundred fatalities. At Sehwan Sharif earlier this year, the shrine of an especially beloved saint or Pir, over 70 devotees were killed by a suicide attack.

Christians have been repeatedly attacked in Pakistan, including at the All Saints Church in Peshawar in 2013 (with 127 deaths), the March 2015 attack in Youhanabad in Lahore (with 15 deaths), and the 2016 Easter attack in Lahore (with 75 deaths). Shia mosques or Imambargahs have regularly seen bloodshed over the years, with dozens of fatalities each year.

The accumulated rage from these and other attacks (especially the Peshawar attack on schoolchildren in December 2014) helped produce the public appetite for a series of military operations against terrorists. The root of sanction that ordinary Pakistanis afforded to those operations was the illegitimacy of the method and target of terror attacks.

Many Indians may see the Anantnag attack as offering a similar window of opportunity to the Indian state to act swiftly and strongly against militants it deems to be anti-national. But in framing and executing a response, India must tread carefully.

One of the reasons for the long tail of violence in Kashmir is because the Indian state has mostly preferred force to dialogue in resolving the many contradictions in that northern province. Decade after decade, this approach has failed. The unanimity and coherence of condemnation that has emerged after the Amarnath yatra attack shows that many Kashmiri separatists are actually politicians whose need to be seen as legitimate actors is very high. A conversation with such people is always possible.

India needs to have this conversation, with Kashmiris – especially since India’s leaders seem to have already decided that it does not intend on having that conversation with Pakistan.

Pakistan is enduring a unique political moment in its long and arduous road to democracy, and an elected (and corrupt) prime minister is once again facing an uncertain future. The volatility in Pakistan may offer India a unique opportunity to engage Kashmiris in a sincere conversation about Kashmiri identity.

Using the Anantnag attack to try to bulldoze elements of this identity that may not recognize India as their sovereign would be a mistake. Bad people with the intention to hurt innocent citizens, including women and children, may be waiting in the wings to take advantage of such mistakes.

For years, Pakistanis have been successfully convinced of the normative importance of supporting Kashmiris of all ilk — the human rights violations at the hands of the state helps sustain this normative conviction. But as victims of senseless violence against worshippers itself, ordinary Pakistani opinion could be poised to be less spoiler and more concerned onlooker. Indians and Pakistanis – and Kashmiris and Sindhis and Baloch — we are all victims of the bad people that have made bloodsport of the religious devotion of South Asians.

The cycle of past violence must inform a less violent future for Kashmiris. Indians are quick to blame Pakistan for always taking advantage of the grievances of Kashmiris. The aftermath of this latest attack may offer a new opportunity for India. Is India prepared to take it?